According to the Philippine Heart Association Survey, the incidence of coronary artery disease among hospitalised Filipino people is 17.5%, with an estimated mortality of 6.5%.1 It is one of the most common causes of death and is increasing. Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) is usually classified as ST-elevation MI (STEMI) or non-ST-elevation MI (NSTEMI). Because time is of critical importance, prompt reperfusion therapy is central and crucial. Based on the European Society of Cardiology guidelines for STEMI, primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is recommended over fibrinolysis within the indicated time frames; for high- and very high-risk NSTEMI, an early and immediate invasive strategy is indicated.2,3 This highlights the importance of PCI-capable hospitals.

To minimise delays, the organisation of STEMI treatment into networks is recommended. A clear definition of the geographic areas of responsibility among PCI-capable hospitals is an important feature. It is based on the location and accessibility of healthcare services to the people living nearby.4 While there is no agreement about how to best define this, the shortest travel time to destination method can be used.5 An understanding of geography and transport is therefore fundamental.

The Philippines is comprised of 7,641 islands, with an estimated total land area of 300,000 km2. It is divided into 82 provinces, including Metro Manila, and three main island groups: Luzon (39 provinces), Visayas (16 provinces), and Mindanao (27 provinces).6 The transport system comprises road, waterways, air travel and railroads. The majority of transport is via road, but water and air transport are also important.7 The Land Transportation and Traffic Code establishes speed limits of 100/80/40/30 km/h depending on road type and prevailing circumstances.8 However, emergency vehicles may exceed these limits. Sea and air ambulances offer faster transportation and are not affected by road traffic conditions, but are less readily available and entail higher costs.

In Europe, the STEMI network relies on close cooperation between emergency medical systems and well-distributed PCI-capable hospitals, prehospital fibrinolysis and organisation within surrounding rural areas with short transfer times.9 Locally, the Heart of Batangas STEMI program uses the hub and spoke model, which provides PCI with 24/7 cardiac cath lab services in their province.10 However, there is currently no regional/nationwide STEMI network or emergency medical system in place and the likely first medical contact of a STEMI patient would be in a non-PCI-capable hospital.

The mode of reperfusion therapy will depend on the maximum expected delay: if ≤2 hours, the patient should be transferred for primary PCI; if >2 hours, a fibrinolytic strategy is recommended.11 Identifying the geographic areas of responsibility among PCI-capable hospitals will shed light on the current status of the ACS healthcare system, possible unmet needs and recommendations for improvement. The objectives of this study were threefold: to describe the characteristics of PCI-capable hospitals in the Philippines; to describe the locations of interventional cardiologists in the Philippines; and to illustrate the geographic areas of responsibility among PCI-capable hospitals in the Philippines.

Methods

We conducted a descriptive study using demographics obtained from the Philippine Statistics Authority, along with the list of registered PCI-capable hospitals and the total number of adult interventional cardiologists per island as of January 2022 obtained from the Philippine Society of Cardiovascular Catheterization and Interventions.12 We used Map Developers (www.mapdevelopers.com) to mark the exact location of each PCI-capable centre and drew a 120 km radius around each PCI-capable hospital (Figure 1). The choice of a 120 km radius was based on the average of 60 km/h from the Land Transportation and Traffic code multiplied by 2 hours to account for the maximum expected delay from STEMI diagnosis to primary PCI. The maps of the geographic area of responsibility and provinces (Figure 2) were overlaid using Microsoft PowerPoint version 2021 and categorised as covered, partially covered or not covered (Figure 3).

Operational Definitions

The operational definitions used in the study were as follows:

- STEMI diagnosis: disposition based on symptoms consistent with myocardial ischaemia and typical or atypical ST-elevation ECG criteria.

- PCI-capable hospital: an institution that offers PCI for ACS patients.

- Geographic area of responsibility: a 120 km radius around a PCI-capable hospital.

- Covered: the whole province is within any radius.

- Not covered: the whole province is outside of any radius.

- Partially covered: province is partly inside and partly outside any radius.

- Main location: the address where a PCI-capable hospital is located.

Data Organisation, Editing, Processing and Analysis

The data obtained were listed and categorised using Microsoft Excel version 16.38. Data were rechecked twice to ensure correctness and validity.

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were performed using Microsoft Excel version 16.38 and descriptive statistics tools. Frequency, percentage and ratio were used to summarise categorical data. To obtain a simplified ratio, the greatest common divisor (GCD) was calculated, and both the numerator and denominator were divided by the GCD.

Results

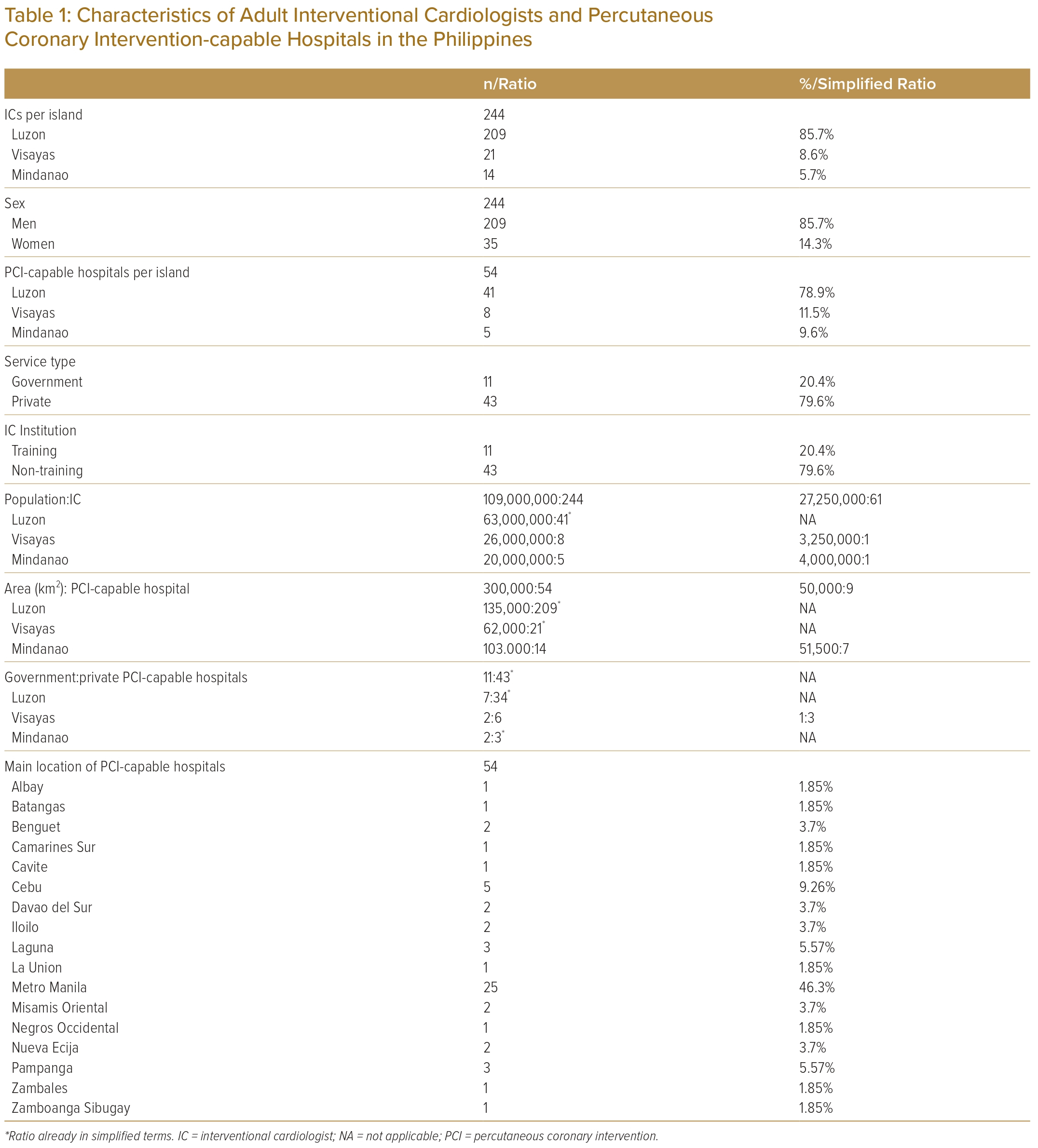

The analysis included 244 adult interventional cardiologists, 54 PCI-capable hospitals, the Philippine population of 109,000,000 people and a land area of 300,000 km2 as of January 2022. A summary of characteristics and notable ratios is shown in Table 1.

The majority of interventional cardiologists were men (85.7%). Luzon registered the highest percentage of interventional cardiologists (85.7%) and PCI-capable hospitals (78.9%). This was followed by Visayas (interventional cardiologists, 8.6%; PCI-capable hospitals, 11.5%) and Mindanao (interventional cardiologist, 5.7%; PCI-capable hospitals, 9.6%). Most PCI-capable hospitals were privately owned (79.6%); 20.4% were government owned. Only 11 of 54 PCI-capable hospitals (20.4%) offered interventional training for adult cardiologists, all of which were in Luzon. Most PCI-capable hospitals were located in Metro Manila (46.3%), followed by Cebu (9.26%), Laguna and Pampanga (5.57%), Benguet, Davao del Sur, Misamis Oriental, and Nueva Ecija, Iloilo (3.7%); the remaining provinces had one or none. The ratio of the Philippine population to interventional cardiologists was 109,000,000 to 244 (27,250,000 to 61 in the simplified ratio). The total area in square kilometres to PCI-capable hospital ratio was 300,000 to 54 (50,000 to 9 in the simplified ratio). The ratio of government to private PCI-capable hospitals was 11 to 43.

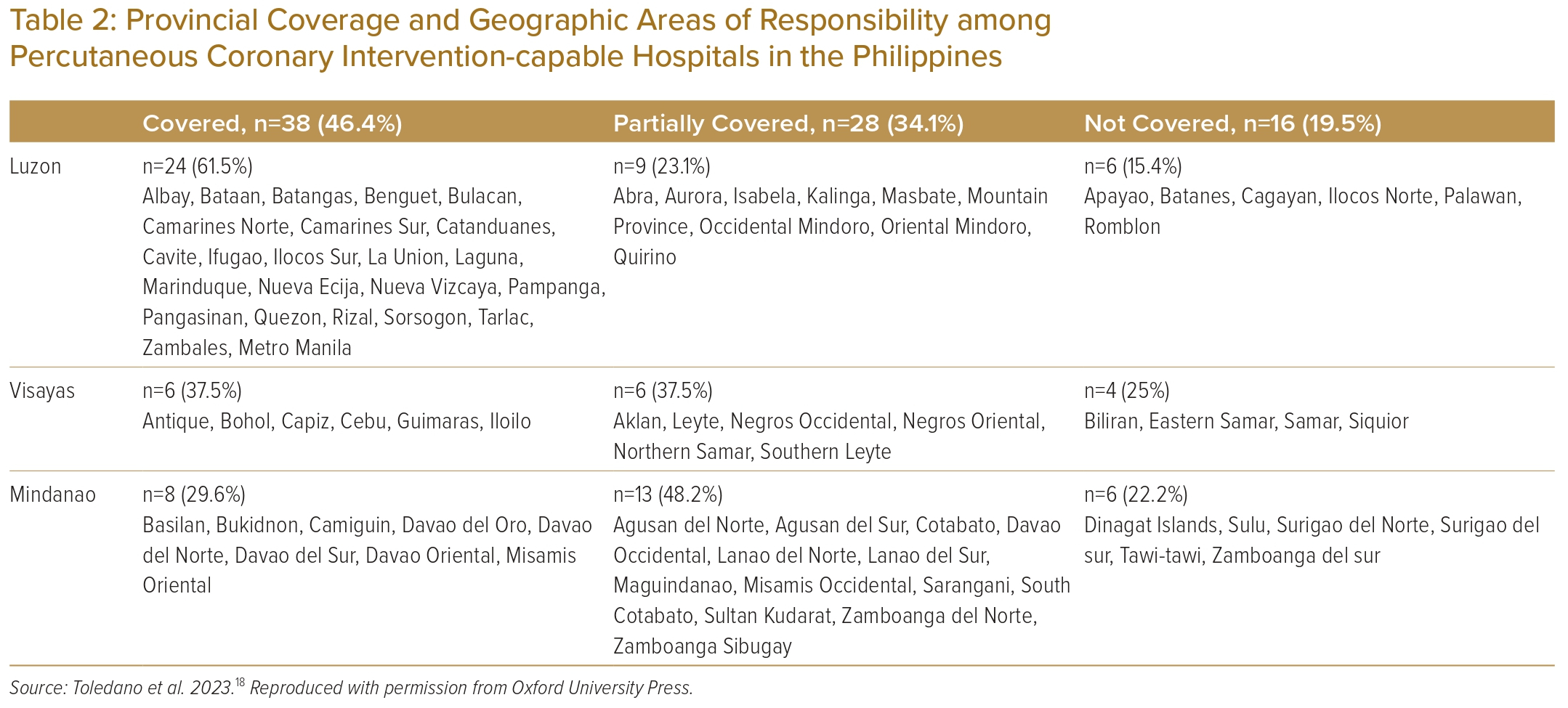

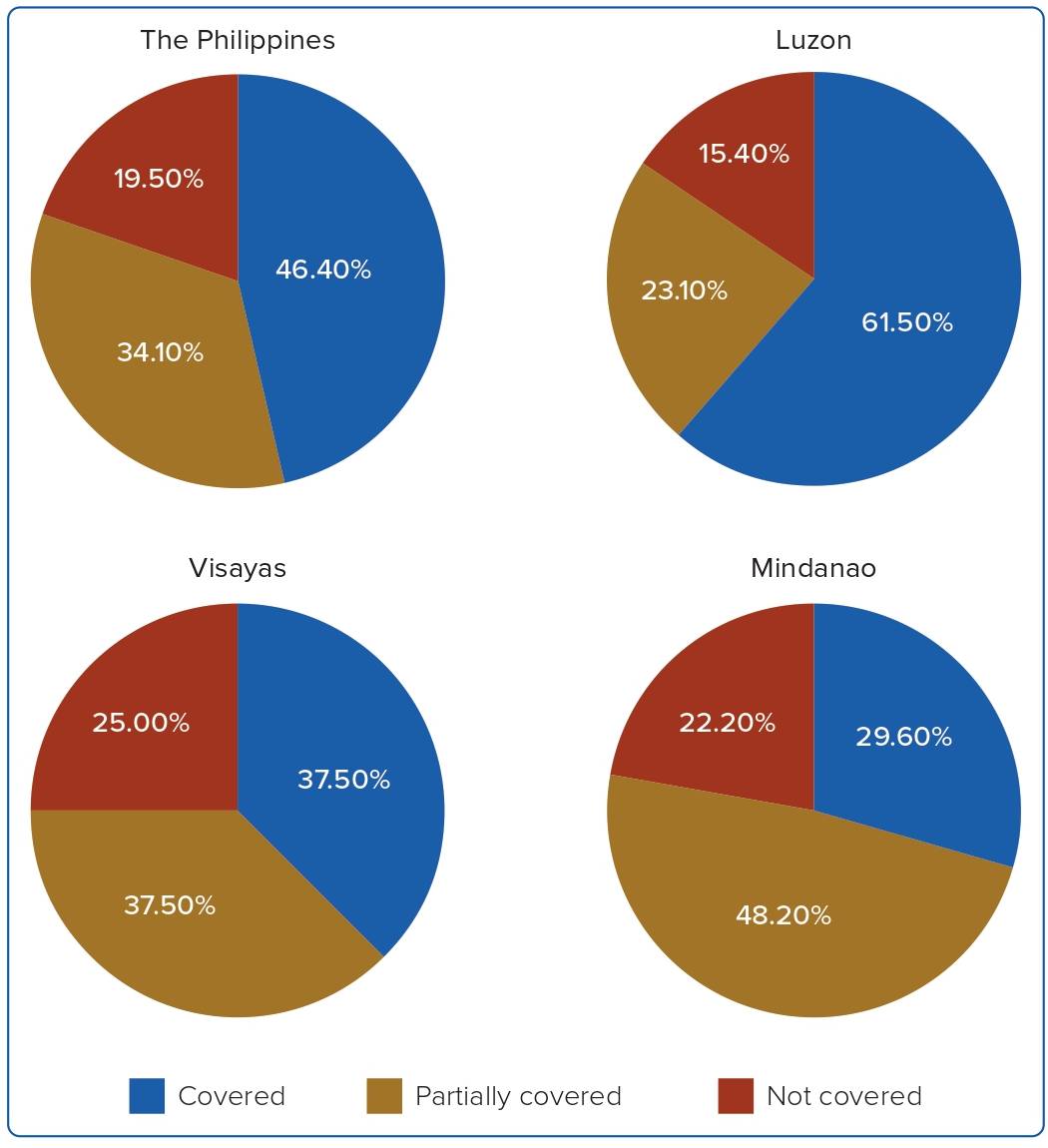

The provincial coverage of PCI-capable hospitals is shown in Table 2 and Figure 4. In terms of coverage, 46.4% of the provinces were classified as covered, 34.1% as partially covered and 19.5% as not covered. In Luzon, 61.5% of the provinces were covered, 23.1% were partially covered and 15.4% were not covered. In Visayas, 37.5% of provinces were equally covered or partially covered, while 25% were not covered. In Mindanao, 29.6% of the provinces were covered, with a significant proportion of 48.2% being partially covered and 22.2% remaining not covered. The specific provinces and geographic areas of responsibility for the entire country are illustrated in Figure 3.

Discussion

The minimum recommended number of interventional cardiologists to provide services in one cardiac cath lab (CCL) is three; for two CCLs, the number is increased to five and for each additional CCL beyond two, an additional interventional cardiologist is required.13

In the Philippines as of January 2022, there were 244 interventional cardiologists serving in 54 PCI-capable hospitals with an average of 1– 2 CCL. At first glance, this may seem sufficient, but there is an uneven distribution among the three major islands. The total population is approximately 109,000,000, so the CCL number appears inadequate when considering the ideal ratio of one CCL per 1,000,000 population.12,14 A significant disparity is observed in Visayas and Mindanao, with ratios of one interventional cardiologist per 3,250,000 and 4,000,000 inhabitants, respectively.

Furthermore, there is a disproportionate ratio between government and private PCI-capable hospitals across all the three main islands. Only a minority of PCI-capable hospitals are government owned and offer training for this subspecialty. This scenario presents challenges in delivering mechanical reperfusion therapy to low- and middle-income patients, as observed in other developing countries.

Luzon had the highest percentage of interventional cardiologists and PCI-capable hospitals. It is the most populous, with an area of 135,000 km2 and an estimated 63,000,000 inhabitants, accounting for 57% of the country’s population.

Mindanao had a lower percentage of interventional cardiologists and PCI-capable hospitals, despite its larger area of 103,000 km2 and a higher population of 26,000,000 representing 24% of the total population. In comparison, Visayas covers 62,000 km2 and has a population of 20,000,000, representing 19% of the entire population.15 This discrepancy is likely to be influenced by factors such as high poverty rates, vulnerability to natural disasters, and conflicts between the Philippines government and armed forces experienced on the island of Mindanao.

Metro Manila is the primary location for nearly half of all PCI-capable hospitals in the country and serves as the site for all except one of the training institutions for interventional cardiologists. It is officially recognised as the National Capital Region and boasts the highest gross domestic product among all the regions.16 Since health financing is mainly driven by out-of-pocket expenditure, an uneven distribution of private PCI-capable hospitals is concentrated in highly urban areas, such as Metro Manila, Cebu, Laguna and Pampanga.

Using the 120 km radius as the geographic area of responsibility, only half of the provinces in the Philippines are covered. Only PCI-capable hospitals located in the centre of Luzon were able to cover more than half of the island. Provinces located in northern and southernmost parts are likely to be partially or non-covered. Patients in provinces such as Batanes, Palawan and Romblon, which are not covered by any PCI-capable hospital, may need to be transported via air or water to reach the nearest PCI-capable hospital.

In the Visayas, PCI-capable hospitals are situated in urbanised provinces of Cebu and Iloilo, which fully or partially cover neighbouring provinces except for the easternmost parts and some provinces separated by waters. Similarly, in Mindanao, PCI-capable hospitals are situated centrally covering the Northern Mindanao and Davao regions. Some provinces are also separated by water and need water or air transport to reach the nearest PCI-capable hospital.

Recommendations

Ideally – in a high resource setting – a STEMI network organised on each island, between non-PCI-capable and PCI-capable hospitals with fully automated wireless transmission of 12-lead ECG, prioritisation and efficient ambulance service either by land, water or air should be established.

In our current setting, the use of a free online global positioning system navigation service that provides real-time traffic updates and an approximation of time arrival can be used to plan transfers. In addition, collaboration with the government regarding the use of land, water, and air ambulance infrastructures should be available to the public. The private and government sectors should also add PCI-capable hospitals that subsidise STEMI cases for low to middle socioeconomic class patients, especially in Mindanao and Visayas islands.17

In terms of the location of new CCls and the use of a pharmaco-invasive strategy, in Luzon, a PCI-capable hospital located in the middle of Kalinga and Cagayan Province may be needed to cover the northernmost part of the island. STEMI patients in Batanes, Palawan, and Romblon will most likely benefit from rapid fibrinolysis. In Visayas, a PCI-capable hospital located in the middle of Samar and Eastern Samar Province may be needed to cover the eastern part of the island. STEMI patients in Siquior and Biliran will most likely benefit from rapid fibrinolysis. In Mindanao, a PCI-capable hospital located in Surigao, and Zamboanga del Sur may be needed to extend its services; in Tawi-Tawi, Sulu and Dinagat provinces, STEMI patients will most likely benefit from rapid fibrinolysis.

Limitations

This is a descriptive study that employed a calculation based on time multiplied by speed to estimate the distance for the geographic area of responsibility. The study did not examine factors such as the type of vehicle, its speed, mode of transport, accessibility, traffic conditions or the proximity of non-PCI-capable hospitals to PCI-capable hospitals, as these were beyond the scope of the research. Although the prescribed speed limits do not apply to emergency vehicles, the 60 km/h used is the average of the speed limits specified for different road types of roads and prevailing circumstances.

Conclusion

In the Philippines, most PCI-capable hospitals are privately owned and centrally located on an island. There may be a need to add PCI-capable hospitals that are government owned, equally distributed and strategically placed in partially and non-covered provinces.

In addition, because of its archipelagic nature, STEMI patients in provinces separated by water and not covered may benefit from rapid fibrinolysis.

Clinical Perspective

- Timely reperfusion is the cornerstone of STEMI treatment.

- In the Philippines, there is no nationwide STEMI network or emergency medical system in place and the likely first medical contact is a non-PCI-capable hospital.

- Defining the geographic areas of responsibility among PCI-capable hospitals will optimise care and minimise delays.