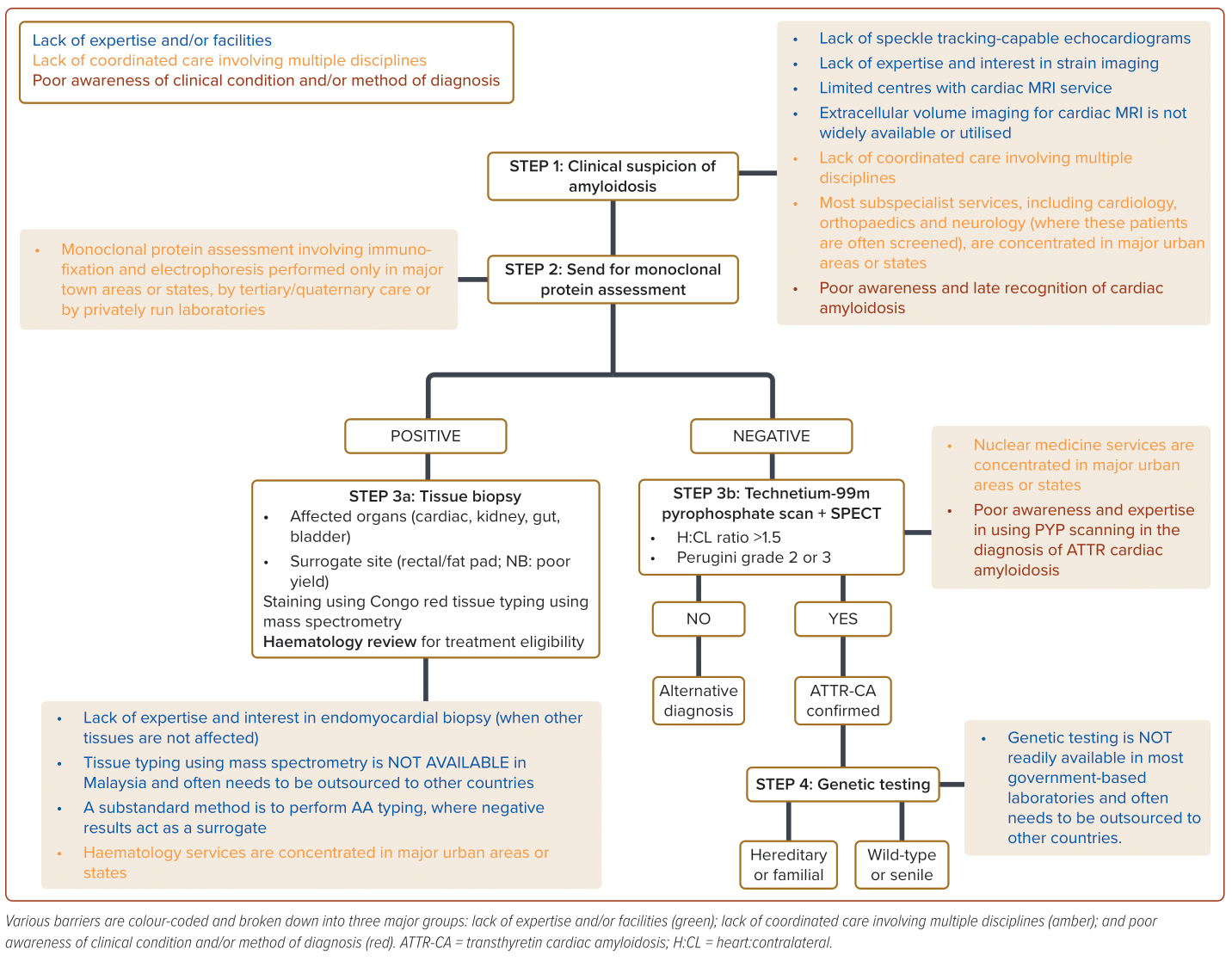

In the past decade, there has been increasing interest surrounding cardiac amyloidosis (CA), partly due to the availability of effective therapies for transthyretin CA (ATTR-CA).1,2 Unfortunately, such progress has been largely limited to developed countries, with little to no progress seen in countries like Malaysia. In fact, clinical pathways in the initial evaluation and management of CA remain sparse in Malaysia, although an Asian consensus document does exist.3 There is a complex interplay between various factors (Figure 1), and using two case examples, we highlight these barriers.

Case 1

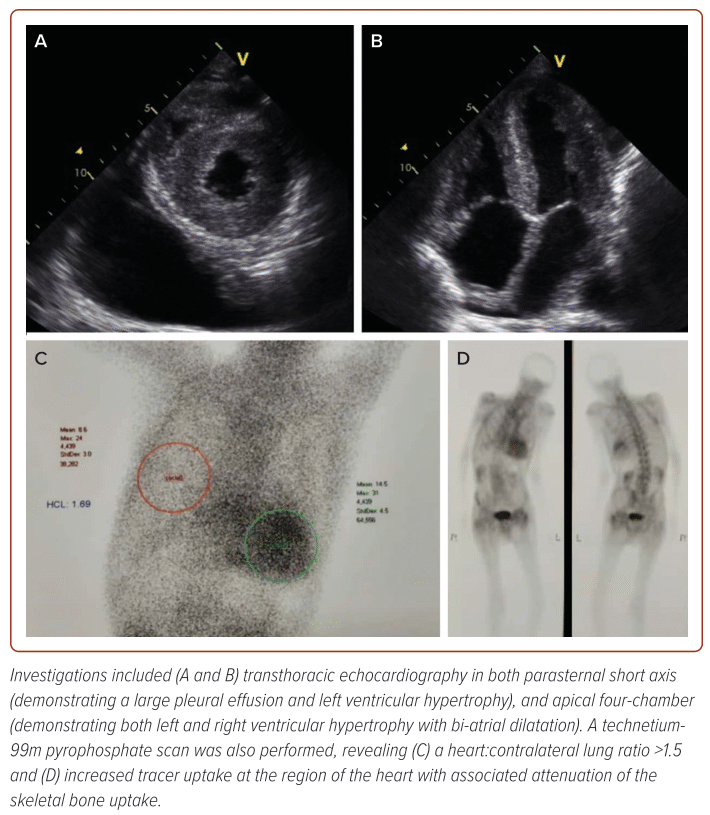

An 81-year-old man presented to a district hospital following an 18-month history of worsening dyspnoea, reduced effort tolerance and peripheral oedema. Clinical examination revealed a blood pressure of 95/68 mmHg with oxygen saturation of 88% on room air. The patient appeared cachectic, with dullness to percussion and reduced breath sounds in the right lower zone of his lungs. Initial N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) was 24,000 ng/l and high-sensitivity troponin T was 78 mmol/l. Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) demonstrated preserved a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of 60%, severe left ventricular hypertrophy (Figure 2) with markedly reduced medial e’ (0.02 m/s) and lateral e’ (0.03 m/s).

The patient was referred to and later reviewed at our clinic 6 months after his initial presentation. A clinical suspicion of CA was raised, leading to a cardiac MRI. Patchy, transmural late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) was seen, but unfortunately, extracellular volume (ECV) quantification was not performed as it was unavailable. Instead, non-conventional dark blood pool sequence was performed revealing diffuse, heterogenous transmural LGE, suggestive of infiltrative disease. Alongside the MRI, monoclonal light chain assessment was performed with unremarkable results, but it accrued a 2-month delay due to being outsourced for immunofixation.

The patient was then referred for a technetium-99m pyrophosphate (Tn-99m PYP) scan which had to be performed externally to the National Cancer Institute due to limited expertise at the centre and neighbouring hospital (Figure 2). The test, which took approximately 3 months to obtain, demonstrated a heart:contralateral (H:CL) ratio of 1.69 and Perugini grade 3, which were highly diagnostic of ATTR-CA.

By that time, the patient appeared more cachectic and was wheelchair-bound; therefore he could not be recruited for any therapeutic-based clinical trial for ATTR-CA as he was unable to demonstrate capability to perform a 6-minute walk test as a prerequisite.

Case 2

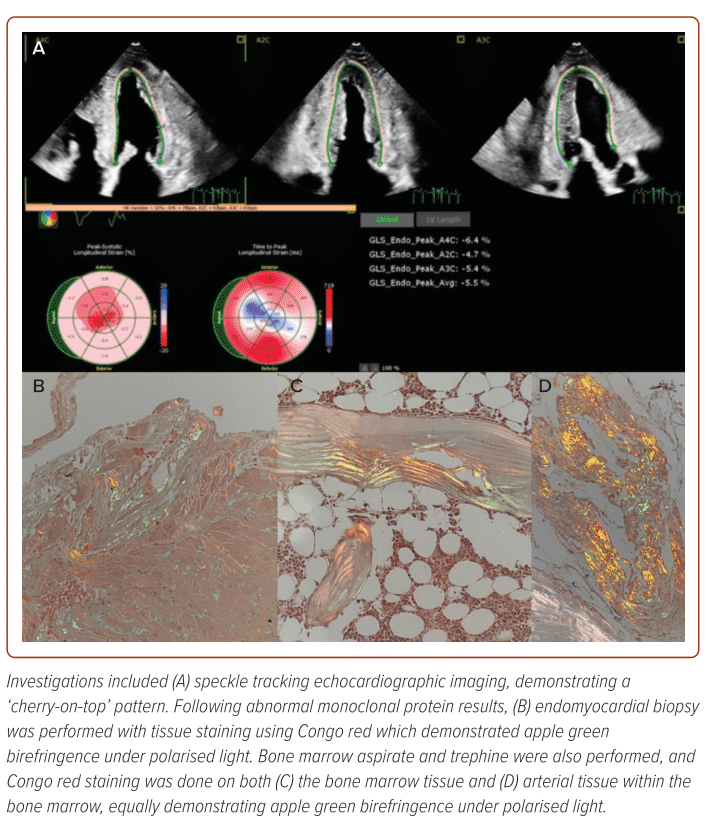

A 64-year-old man with a history of coronary artery disease presented to our centre following worsening dyspnoea over the past 6 months. He had recurrent prior admissions for acute decompensated heart failure. Previous TTE demonstrated preserved a LVEF of 58%, normal LV wall thickness but markedly reduced tissue Doppler imaging average e’ (0.04 m/s). Speckle tracking imaging was also performed, revealing a ‘cherry-on-top’ pattern which prompted a cardiac MRI (Figure 3). The MRI demonstrated patchy, transmural LGE, using non-conventional dark blood pool sequence, raising suspicion of CA.

Initial NT-proBNP was 35,000 ng/l and initial monoclonal protein assessment was performed 8 months prior during his first admission, which showed abnormal serum kappa:lambda ratios. No protein immunofixation or electrophoresis had been performed by the external laboratory, forcing us to repeat the immunological tests with interpretation of the result at a different institution. Repeat test demonstrated evidence of IgM gammopathy, necessitating an endomyocardial biopsy (Figure 3).

Despite initial Congo red staining demonstrating typical apple green birefringence under polarised light, we were unable to perform further typing for light chain cardiac amyloidosis (AL-CA) using either immunohistochemistry or liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectroscopy in Malaysia. Bone marrow aspirate and trephine biopsy only showed findings suggestive of monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance, although there was similar evidence of apple green birefringence under polarised light on Congo red staining (Figure 3).

Following discussions with our haematology colleagues, a decision was made to perform AA typing (for which the patient subsequently tested negative) and Tn-99m PYP scan (to rule out possible ATTR-CA, which showed Perugini grade 1 uptake, with an H:CL ratio of 1.44). The patient was subsequently treated for AL-CA and was started on chemotherapy by our haematology colleagues with ongoing follow-up. Of note, there was an additional 4-month period from biopsy to initiation chemotherapy, as most investigations and laboratory tests were performed outside of our institution.

Lack of Expertise and Facilities

As highlighted in both cases, the current level of expertise and infrastructure available in Malaysia are not built with the care of CA in mind. Issues exist at multiple tiers, with lack of availability in performing strain imaging echocardiography and cardiac MRI across the country, compounded by low usage of speckle tracking imaging and extracellular volume imaging, all of which are useful in screening for infiltrative cardiomyopathies such as CA.2,4 There is also the issue of obtaining endomyocardial biopsies as very few centres are capable of performing the procedure.

Furthermore, interpretation of the histological yield may pose a challenge for most laboratories, in view of how rarely the condition is diagnosed in daily practice. Where there remains suspicion of possible AL amyloidosis following abnormal monoclonal protein assessment, there is no available method of AL typing (both by immunohistochemistry and liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectroscopy) available across Malaysia.1 This leaves only two options: externally source such services outside of Malaysia, which is extremely costly; or more commonly, perform AA typing in which tissue typing with negative result by default would be treated as potentially positive for AL-CA (in the context of abnormal monoclonal protein assessment). However, we know now that CA is by no means dichotomous and rarer forms of the disease have since been reported by various groups worldwide.2,5

Delay in confirmation of diagnosis is often detrimental to patients, especially in those with AL-CA, as prognosis is often poor without treatment, which at present includes disease-modifying chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplant.1,2 In addition, genetic testing, alongside supplementary clinical services such as genetic counselling, is not currently available in Malaysia, which limits the ability to perform cascade screening of familial variants of the disease, although there has been increasing interest in developing these services locally.

Lack of Coordinated Care Involving Multiple Disciplines

Another major challenge in establishing clear pathways for diagnosing CA is the lack of coordinated care between subspecialties. Most subspecialities like cardiology, orthopaedics and haematology are often concentrated in major cities and reviews for external outpatient referrals, anecdotally, can take between 3 and 6 months. Similarly, laboratory-based services, such as monoclonal protein assessment involving immunofixation and electrophoresis, can only be performed by tertiary or quaternary centres, or by privately run laboratories at high cost. Samples are often processed externally which contributes to delays in establishing diagnosis, often at a detriment to patients with potential AL-CA.

Nuclear medicine services and facilities face a similar issue. Only a handful exist across the country, most of which are concentrated in major urban areas or states.

As illustrated here, both patients required Tn-99m PYP imaging for confirmation of ATTR-CA diagnosis and to exclude the same diagnosis even in the presence of abnormal monoclonal proteins with the purpose of overlapping disease in the absence of confirmatory AL tissue typing. Thus, the lack of facilities to perform Tn-99m PYP imaging are a stumbling block in establishing a national-level clinical pathways for CA.

Poor Awareness of the Condition and Accessibility to Treatment

Although there have been noticeable efforts to shed light on CA, many clinicians remain unaware of it, possibly from the old misconception that amyloidosis is a relatively incurable condition. Current access to tafamidis, the only treatment available outside of clinical trials, is very limited largely due to financial implications (costing between RM15,000 [US$3,200] and RM50,000 [US$10,700] per month, per patient).1,2,6

Previous experiences using the medication have been concentrated in major centres, such as the National Heart Institute, and only through ‘compassionate use’ programmes that have since been ceased. In the case of AL-CA, first-line chemotherapy includes bortezemib, cyclophosphamide and dexamethasone, which would cost between RM18,000 (US$3,800) and RM24,000 (US$5,100) for six to eight cycles, which is equally costly.1,2 Autologous stem cell transplantation is performed free locally, although in very few centres. There are also challenges in ensuring appropriate diagnosis of the disease via nuclear imaging, with poor awareness and expertise in using Tn-99m PYP scanning to diagnose ATTR-CA. There have been tremendous efforts in the past few years from industry and the cardiology fraternity in raising awareness surrounding CA. Various scientific statements and consensus papers have also been developed to guide clinicians in the diagnosis, evaluation and management of CA.1–3

Light at the End of the Tunnel

Despite all the challenges, there is hope in improving care pathways to ensure early diagnosis and recognitions of CA in Malaysia. Building an amyloidosis network may be a good starting point, allowing for exchange of ideas and experiences between various centres to facilitate referrals for pivotal pathological and radiological services across the country. The onus is on clinicians to improve the way we communicate with one another, which undoubtedly impacts the way we care for our patients.

Clinical Perspective

- Clinical pathways for cardiac amyloidosis are haphazard in Malaysia.

- Contributing factors include lack of expertise, coordinated care and poor awareness.

- An amyloidosis network may allow for exchange of ideas and experiences between various centres locally.