The decision to have coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) is often a major one for patients with ischaemic heart disease. The availability of a less invasive alternative, such as percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), may add further considerations to the decision-making process, especially from the patient’s perspective.

Patients recommended for revascularisation with CABG include those with >50% stenosis of the left main (LM) artery, triple vessel disease (TVD), complex multivessel disease (MVD) defined as having a SYNTAX score ≥22, or patients with diabetes and MVD. The American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines recommend CABG over PCI in these patients because of better outcomes, such as lower rates of MI and mortality in patients with TVD, and lower major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events (MACCE) rates, cardiac death and need for repeat revascularisation in patients with diabetes and MVD.1–5 CABG has been associated with superior survival outcomes for patients who are indicated and suitable for CABG compared to PCI due to fewer repeat revascularisations and lower mortality.3,6,7

Despite the benefits associated with CABG over PCI, it appears to be relatively underused.1 One randomised controlled trial found that patients with TVD elected to undergo PCI more often instead of CABG despite CABG being associated with lower occurrences of MACCE.8 This finding is also replicated in hypothetical scenarios where the risk of PCI was arbitrarily doubled and patients were asked to choose between PCI or CABG. Despite the elevated risks, PCI was chosen more frequently over CABG, suggesting that patients have a predilection towards the less invasive option even if associated risks are markedly elevated.9

Given the underuse of CABG despite its known benefits, there is a surprising lack of studies examining the reasons given by patients and surgeons for declining CABG. The primary aim of this study is to describe the reasons why patients who meet indications for CABG do not end up having the procedure from both the patients’ and surgeons’ perspectives. Findings can be used by physicians to address patient concerns regarding CABG and provide patients with true informed consent. Understanding patients’ reasons for rejecting the procedure can also improve physician/patient communication and inform counselling for patients to help them choose the intervention that would be most beneficial. Identifying surgeons’ reasons for rejecting CABG for patients can help us evaluate if our current risk models are comprehensive and can be used to inform future guidelines.

Methods

This study was a retrospective observational cohort study. All patient data were obtained from a single centre audit database from a tertiary cardiovascular referral centre with Singapore’s highest CABG volume from 2018 to 2020. This study was exempt from review by the Central Institutional Review Board (CIRB ref=2010/544 C).

A total of 301 cases were reviewed by three independent reviewers. The cases were obtained from a database of patients who underwent catheterisation or PCI and the first 301 cases were selected consecutively. Inclusion criteria were patients who were offered CABG as documented in the clinical notes but who eventually chose not to have the intervention. Exclusion criteria were patients who had not been offered CABG. All included patients who rejected CABG eventually underwent PCI. All patients were followed up for 2 years.

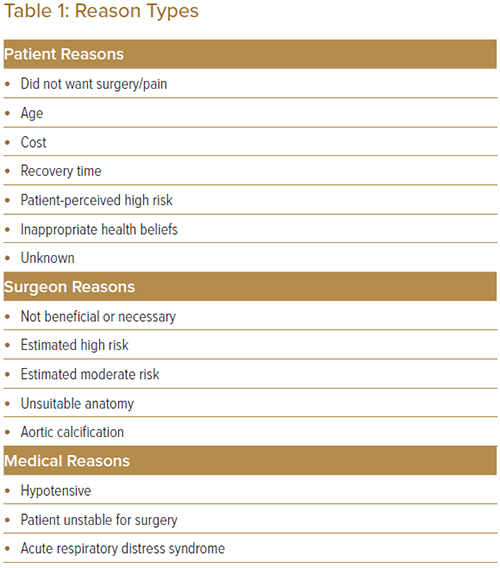

Three independent reviewers extracted the data for the first 50 cases and inter-rater reliabilities (IRRs) were assessed. Each set of data was coded twice. One reviewer coded all 301 cases and two independent reviewers coded 150 and 151 each as a second round of review. All discrepancies between the two raters were discussed to agree upon a final theme. If the two raters could not come to an agreement, the third rater, who did not initially review the case, was consulted to resolve the discrepancy and agree upon a final theme. Finalised theme(s) for why patients did not undergo CABG were identified for each case. The reasons were classified broadly into three main reason types: patient reasons, surgeon reasons and medical reasons. These reasons were further classified into subcategories to elicit more specific concerns (Table 1).

Several a priori criteria were preset. First, for some cases, it was unclear whether patients rejected CABG for patient-driven reasons or because the surgeon quoted a risk level that was deemed to be prohibitive. Patients who rejected CABG for reasons that were unrecorded or no reason had been documented and who were also quoted as being high risk by surgeons were classified under surgeon reasons. Second, there were some patients who were not referred to the cardiothoracic surgeon (CTS) for CABG because they specifically requested not to be referred as documented in either clinical notes or coronary angiography reports. We included these cases as the option for CABG had been offered. Third, as medical reasons and surgical reasons have some intrinsic overlap, for the purpose of this study we only considered reasons which were explicitly CABG-related as surgeon reasons. Other reasons, such as haemodynamic instability or subsequent medical deterioration, were considered as medical reasons and not surgeon reasons as these patients may not have been medically suitable for any procedure.

To compare surgeons’ perception of high risk against the patients’ objective risk scores, we used the EuroSCORE II (Supplementary Material Table 1) – an objective measure of in-hospital mortality after cardiac surgery – of patients who were deemed to be high risk by surgeons against patients in the other categories.10

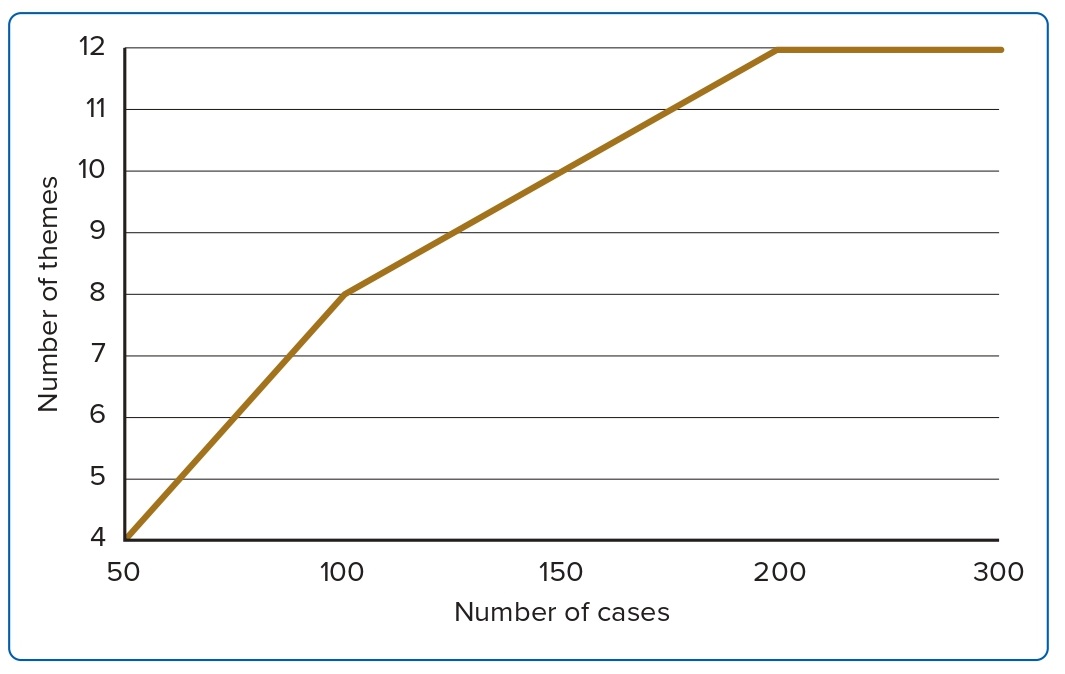

An initial arbitrary sample size of 301 was established. To determine if the sample size was sufficient, the data were analysed for saturation. If the data had not reached saturation, more cases would be reviewed until data saturation was reached. Data saturation is defined as the point in coding where no new themes emerge from the data.11 To check for saturation, we used a base size of 100 cases and a step size of 50 and assessed for the number of unique themes.

Fleiss’ κ was conducted to assess the degree of agreement among the three independent reviewers using the IRR package in RStudio. Next, the reasons identified for all cases who were referred to CTS but did not undergo CABG (n=127) were coded into categories and descriptive statistics were conducted. Reasons were first divided into patient, surgeon or medical reasons and frequency counts and percentages were reported. Following this, the frequency counts and percentages of each subcategory were reported within each reason type. Patients who rejected CABG with reasons not explicitly stated were classified as ‘reason unknown’.

To compare the subjective risk perception with established objective risk scores, an independent T-test was conducted to compare the EuroSCORE II of patients recorded as being high risk by surgeons against those who were not considered high risk. According to the traditional criterion for EuroSCORE, low is between 0–2.99, intermediate between 3–5.99, and high is more than 6. We adopted the same criteria for the EuroSCORE II.12 A chi-square test was also conducted to determine the relationship between the EuroSCORE II of patients who were deemed high risk by surgeons against those who were not. Percentages of patients with a low, intermediate and high EuroSCORE II were presented for patients who were quoted high risk by the surgeon.

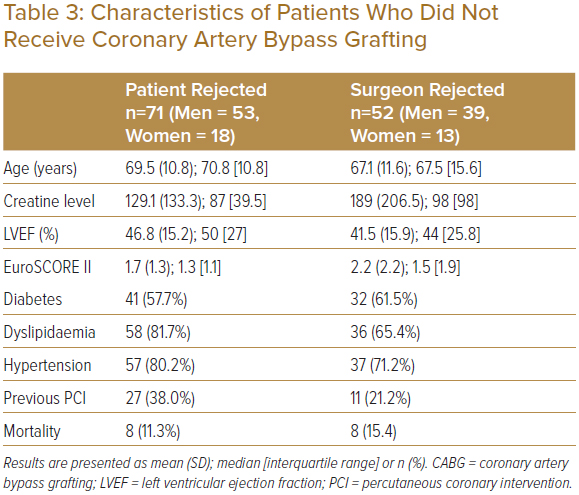

Descriptive statistics of patients who rejected CABG and those patients whose surgeons had rejected CABG were also reported. Baseline characteristics examined include age, creatinine level, left ventricular ejection fraction, EuroSCORE II and presence of diabetes, dyslipidaemia, hypertension, previous PCI and mortality. All categorical data were reported as frequency counts and percentages; continuous data were reported as mean (±SD) and median (interquartile ratio [IQR]), as appropriate. Comparison between categorical and continuous data was conducted using χ2 tests and independent T-tests, respectively.

All statistical analyses were conducted using statistical software R version 4.0.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing), RStudio version 1.3.1093 (RStudio) and Microsoft Excel (Microsoft).

Results

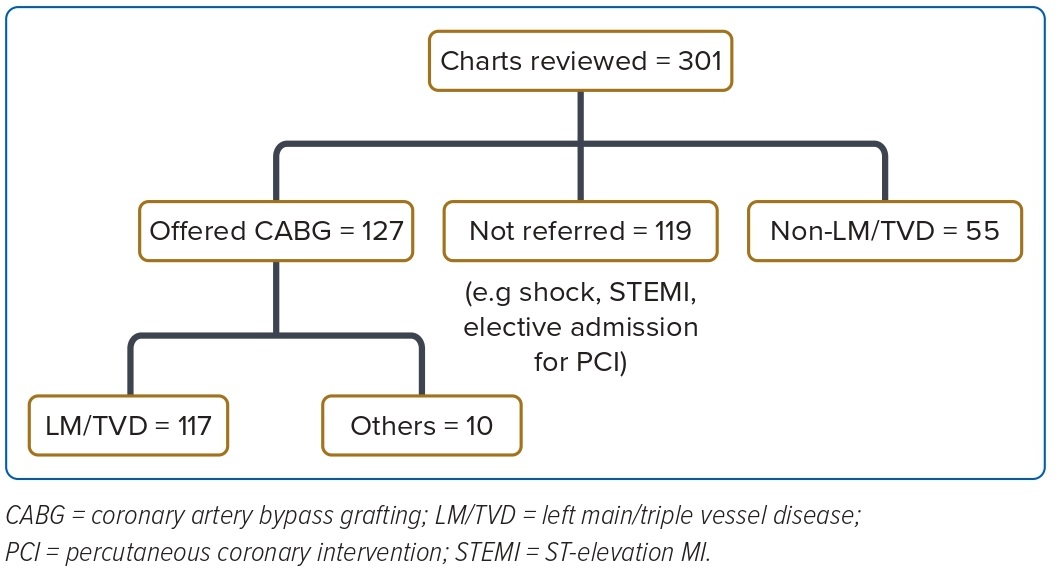

A total of 301 patient charts were reviewed (Figure 1). Of these, 127 patients were referred for CABG, 119 patients were not referred due to reasons such as shock, ST-elevation MI or were electively admitted, and 55 patients did not meet indications for referral (non-LM/TVD). Of the 127 patients referred for CABG, 117 had LM and TVD and the other 10 did not meet the criteria, such as having dual vessel disease. Patients were considered to have LM and TVD if they had ≥50% stenosis of LM, or ≥50% stenosis of proximal or mid-left anterior descending, left circumflex and right coronary artery, respectively, or were indicated to have LM or TVD in catheter reports. The main theme of the reason for rejecting CABG was identified for each patient referred for CABG by three independent raters. The κ of the three independent raters in this study was 0.83 (p<0.00) and demonstrated an almost perfect degree of agreement. Furthermore, a Fleiss’ κ of 0.83 is also comparable to the κ of other similar medical chart review studies, with κ values of 0.7, 0.86, 0.61 and 0.62.13,14

Eight unique themes were identified in the first 100 cases. In the next 50 cases, cases 101–150, there were two unique themes. In the next 50 cases, 151–200, there were also two unique themes. We completed all 301 cases and the data yielded no unique themes after case 180 and the data was deemed to be saturated (Figure 2). A total of 12 surgeon and patient subcategory themes were identified.

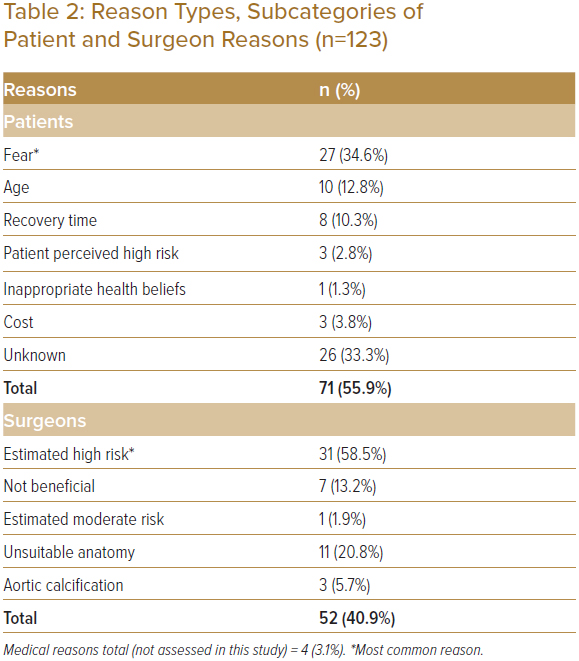

The proportions of identified reason types are shown in Table 2. Of the 127 patients, the majority of patients (56%, n=71) declined CABG due to patient reasons, whereas for 41% of patients (n=52) CABG was declined by the cardiothoracic team. The remainder of the patients did not have CABG due to medical reasons (n=4).

Six subcategories of patient reasons were identified from the chart reviews – age, cost, not wanting surgery or pain, inappropriate health beliefs, a high perceived risk, and long recovery time. The total subcategories identified (n=78) were more than the number of patients who rejected CABG as some patients had more than one reason. Of the patients who rejected CABG, 34% did not specify the reason (n=26). Out of the cases with a specified reason, 52% (n=27) declined CABG because they did not want surgery or pain, 19% (n=10) because of age, 15% (n=8) because of long estimated recovery time, 6% (n=3) because of cost, 6% (n=3) because of high perceived risk and 2% (n=1) because of inappropriate health beliefs.

Among the 53 patients who were declined CABG by the surgical team, five subcategories of reasons were identified – surgeon deemed the intervention to not be beneficial or necessary, surgeon deemed the patient to be high risk, surgeon deemed the patient to be moderate risk, unsuitable anatomy and aortic calcification. The most common reason for a surgeon declining CABG was due to a perceived high risk of patient mortality (59%, n=31). Among the other patients, 21% were rejected due to unsuitable anatomy (n=11), 13% were deemed not beneficial or necessary to have CABG (n=7), 6% had aortic calcification (n=3), and 2% were seen to have moderate risk (n=1). Table 1 illustrates the themes identified and Table 2 describes the frequency and percentages of the identified patient and surgeon reasons.

For patients who were declined CABG due to perceived high risk by the surgeons, a comparison with the patients’ objective risk score was conducted. The EuroSCORE II of patients said to be high risk by surgeons (n=31) had a mean (SD) of 2.67 (2.66), whereas all other patients who were not quoted high risk had a mean of 1.72 (1.33). The difference between EuroSCORE II of those quoted as high risk and those not quoted high risk was not significant (p=0.065). Among the patients who were deemed high risk by the surgeon and as a result were declined and did not receive CABG, 71% (n=22) had a low EuroSCORE II. The remaining 23% (n=7) had an intermediate EuroSCORE II and only 6% (n=2) had a high EuroSCORE II.

The characteristics of patients who declined CABG (n=71) are presented in Table 3. The mean (SD) age of patients who declined CABG was 69.5 (10.8) years, LVEF was 46.8 (15.2), creatinine levels were 129.1 (133.3), and EuroSCORE II was 1.7 (1.3); 82% (n=58) of patients had dyslipidaemia, 80% (n=57) had hypertension, 57% (n=41) had diabetes, and 38% (n=27) had a prior PCI (Table 3). Of the patients who rejected CABG, 11% (n=8) had deceased.

The characteristics of patients whose surgeon declined CABG (n=52) are presented in Table 3. The mean (SD) age of patients who declined CABG is 67.1 (11.6) years, LVEF was 41.5% (15.9), creatine level was 189 (206.5), and EuroSCORE II was 2.2 (2.2). There were 36 patients (65%) with dyslipidaemia, 71% (n=37) had hypertension, 62% of patients (n=32) had diabetes, 21% (n=11) had a prior PCI and 15% (n=8) had deceased (Table 3).

Discussion

Our study found that surgical reasons for rejecting CABG occurred almost as frequently as patients’ reasons, highlighting the need to explore surgeon’s concerns which are relatively underinvestigated in the existing literature. Furthermore, it was also elucidated that most of the patients deemed high risk by surgeons did not have a commensurate high risk determined by their EuroSCORE II. There was also no significant relationship between subjective risk quoted by surgeons and objective risk scores. This suggests that current risk scores may insufficiently encapsulate surgeon concerns, with some concerns not being measured by objective risk scores.

Patients had several main concerns about CABG, such as fear of pain, age, and recovery times. In light of this finding, future interventions could improve awareness and inform counselling by addressing specific concerns about surgery. Specific information targeted towards these areas could be included during clinic consultations or in medical brochures. Patients can also be connected with peer support groups with patients who have undergone CABG to provide a patient-oriented perspective in addressing fears of pain or long recovery times. Adopting educational approaches targeted at these specific concerns may be more effective in helping patients choose the most suitable treatment modality. With proper patient education, true informed consent can be achieved.

While existing studies show that patients and surgeons select PCI more often than CABG, the reasons for doing so are unclear. Our findings are in line with existing evidence comparing the preferences for PCI and CABG, and uncovered concrete reasons for rejecting CABG through retrospective chart reviews in the local clinical context. It has been well documented that CABG is being recommended less often than guidelines suggest.15 Among patients indicated for CABG, catheter laboratory cardiologists referred only 53% of them for CABG and 46% were referred to PCI and/or medical therapy.15 Even in patients who were indicated for both CABG and PCI, 93% were referred to PCI.15 In arbitrary settings, patients prefer PCI over CABG even if risks are artificially increased, and the awareness of higher accompanying risks associated with PCI compared to CABG did not deter them from choosing PCI.16 This predilection for PCI has been shown to occur even when surgeons and cardiologists are presented with hypothetical scenarios to choose between recommending PCI or CABG.16 However, the reasons behind a preference for PCI over CABG have not been clearly elucidated. While patients were generally found to have an inflated perception of the risks associated with CABG, which could be due to anxiety and fear of raised invasiveness and longer recovery times, the evidence is largely speculative and has not been established in our local context.16–19 While it has been suggested that particular risk factors, such as risk of death or stroke and bleeding, have greater weight than other risk factors in patient decision-making, studies exploring actual reasons for CABG rejection derived from clinical documentation are scarce, hence the value of our study.16,20

Existing studies show that even though surgeons prefer PCI less often than patients and give a relatively more objective risk estimate when compared to patients, they often give higher risk estimates of surgery compared to objective risk scores.16,21 This was found to be true in our clinical setting, as among the patients described as being at high risk by surgeons, the majority were low risk on the EuroSCORE II. While risk assessments by surgeons should extend beyond traditional risk scores to consider the complex interplay of patient factors and comorbidities, objective risk scores for surgical risks have been frequently used to complement surgeon decisions, with EuroSCORE and EuroSCORE II being two of several available.10,12,22 However, there are some limitations to the use of objective risk measures. First, it was found that surgeon perceptions of risk are often conflated when compared to the EuroSCORE for CABG patients, as risk models may not sufficiently capture components that concern the surgeon and that the subjective prediction by surgeons is often more accurate in its prediction for outcomes up to 180 days post-surgery.21 Second, EuroSCORE II has a tendency to underestimate mortality of patients post-surgery and we sought to see if this was true in our practice setting.23 What we found was congruent, as among those rejected by surgeons for CABG and referred to PCI due to surgeon perception of high risk, a majority had a contradictory low EuroSCORE II, indicating that the EuroSCORE II did not sufficiently capture the concerns of the surgeons. This suggests that there could be surgeon concerns that are not addressed in the EuroSCORE II, with possible examples being porcelain aorta, frailty and chest radiation.24–26 Elucidating these areas of concern in future studies would be helpful when considering future guidelines and measures.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. While we attempted to clearly define individual categories by setting a priori definitions and criteria, it is difficult to separate certain categories with inherent overlaps. For example, medical reasons and surgeon reasons have a degree of overlap as surgeons are more likely to reject CABG if the patients are medically unstable. Hence, for our study, we classified the reasons directly related to CABG as surgeon reasons. It was also difficult to ascertain whether patients who were considered to have high and moderate risk by surgeons declined surgery because of their own reasons or they were influenced by the surgeon’s estimated risk. For these instances and for the purpose of this study, if the patient’s chart had a specific patient reason unrelated to the risk quoted, we classified them under patient reasons. However, for those with no patient reasons or if the patient’s reason was ‘unknown’, we categorised them as surgeon reasons as it was unclear if the patient rejected the intervention due to their own reasons or the estimated risk. Finally, due to the nature of retrospective chart reviews, there are some missing data as some cases did not have reasons documented.

Conclusion

Our study has identified several reasons patients might reject CABG and this can inform patient counselling. Educational strategies can be further refined to address patient concerns and direct patients towards the treatment that would be most beneficial for them. Future studies could employ other methods, such as interviews or questionnaires, to find more detailed information about patient and surgeon perspectives to overcome the inherent limitations of chart reviews. The disparity between surgeon perception and the EuroSCORE II also prompts investigation to identify areas where surgeons’ concerns are not covered by existing risk tools. Further studies could also compare subjective risks against objective scores in a larger population.

Click here to view Supplementary Material.

Clinical Perspective

- Pertinent patient and surgical reasons for declining coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) were identified.

- Identifying patient reasons for declining CABG can guide appropriate patient counselling and direct patients to interventions with the most favourable clinical outcomes.

- The disparity between subjective and objective risk scores suggests that current measures do not fully capture surgeons’ risk concerns about CABG.