Worldwide, the prevalence of non-communicable diseases, including cardiovascular diseases (CVDs), is increasing at a staggering rate. CVD is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality, attributable to an increase in risk factors such as obesity, diabetes and hypertension.1 The Philippines is not exempt. In the Philippines, the most common causes of morbidity and mortality in the four decades before the 1980s were infectious diseases, such as tuberculosis, pneumonia and gastrointestinal infections.1 Towards the middle of the 1980s, non-communicable diseases, comprising diseases of the heart and vascular system, overtook infectious diseases as the most common causes of morbidity and mortality.1 Hypertension has become the most common and preventable risk factor for CVD.2,3 Poor control and inadequate treatment of hypertension has led to an increase in the incidence of hypertension-related complications such as stroke (ischaemic or haemorrhagic), ischaemic heart disease, vascular diseases and chronic kidney disease. An analysis of worldwide data suggested that the number of adults living with hypertension would increase from 1 billion in 2000 to 1.56 billion by 2025.4 Hypertension, defined as blood pressure 140/90 mmHg or greater, is a multifactorial and highly complex disease, with evidence suggesting that those living with it are mostly asymptomatic, meaning that hypertension can remain undetected for a long period.5 Risk factors for hypertension include excessive salt intake, obesity, increased alcohol consumption and a sedentary lifestyle.6–8 When diagnosed early, hypertension is managed by lifestyle changes and pharmaceutical intervention. However, poor adherence to and compliance with treatment are considerable challenges to hypertension control.8

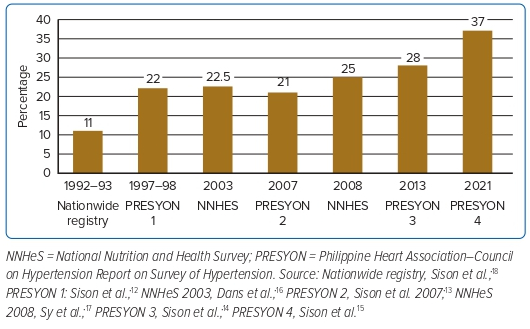

In the Philippines, CVD is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality, with hypertension identified as one of its risk factors.1 The prevalence of hypertension is steadily increasing, from 11% in 1992 to 25% in 2008.1 Drug treatment and compliance rates have improved, but blood pressure control remains low during the same period. A survey conducted by the Food and Nutrition Research Institute of the Department of Science and Technology in 2018 found that the prevalence of hypertension in the Philippines had decreased to 19.2%.9

Epidemiology of Cardiovascular Disease and Hypertension in the Philippines

Since the mid-1980s, non-communicable diseases, with CVD being the most prevalent, have overtaken infectious diseases in the Philippines as the most common causes of morbidity and mortality.¹ Despite these reported findings, no studies or surveys were conducted in the Philippines and there were no nationwide data on hypertension and related CVDs prior to the 1990s. With these developments and the paradigm shift in the top causes of morbidity and mortality in the country, the Philippine Heart Association (PHA), the national cardiac organisation of the Philippines, embarked on studies to evaluate the real status of CVD and the risk profile among Filipinos. The objectives of these studies were to determine the risk profiles of Filipinos with hypertension and CVDs, including stroke and chronic renal disease, and to determine the unmet management needs of these hypertensive individuals. Based on a target organ survey among hypertensive Filipinos conducted by the PHA–Council on Hypertension in 1996, more than half (58%) the hypertensive population surveyed had target organ damage.10 The most common organ damage seen was cardiac damage (45%), consisting of left ventricular hypertrophy, coronary artery disease and heart failure, followed by kidney damage (17%), consisting of hypertensive nephropathy (azotaemia, microalbuminuria, macroalbuminuria, end-stage renal disease), and brain damage (16%), consisting of transient ischaemic attack and previous stroke (ischaemic or haemorrhagic).10 Another survey conducted by the PHA–Council on Hypertension involved patients admitted to hospital for any cause.11 In that study, CVD and infectious diseases were the most common diseases responsible for the hospitalisation of patients. Among the hospitalised patients with CVD, hypertension was the most common risk factor or comorbidity (38.6%) identified, followed by stroke (30%), coronary artery disease (17.5 %) and heart failure (10.4%).11 Cognisant of the fact that hypertension is the most common risk factor present among Filipinos hospitalised with CVD, the PHA has since conducted a series of hypertension prevalence studies, dubbed the PHA–Council on Hypertension Report on Survey of Hypertension (PRESYON) studies.

Methodology of the PRESYON Studies

The PRESYON studies were well designed. These studies were prospective, multistage, stratified, nationwide surveys on hypertension. Field researchers were recruited and trained by an independent professional survey group. The field researchers were retrained by members and officers of the PHA–Council on Hypertension to ensure their clinical efficiency in detecting hypertension and comorbidities during interviews, using validated questionnaires to establish a history of diabetes, stroke and angina and claudication to determine the presence of peripheral vascular disease. Field researchers were equipped with battery-operated oscillometric blood pressure monitors calibrated and validated by the Philippine Society on Hypertension, portable weighing scales and tape measures for anthropometric measurements BMI, waist-to-hip ratio (central obesity), portable electrocardiograph machines and point-of-care microalbuminuria testing kits. These measurements comprise screening procedures for end organ survey. These tools were to be used only with individuals detected to have hypertension.

There were five stages in sample selection in the PRESYON studies. Stage 1, selection of sample province; Stage 2, selection of sample cities/towns in each sample province; Stage 3, selection of sample barangays (local communities) in each sample city; Stage 4, selection of sample households in each sample barangay; and Stage 5, selection of one respondent from each sample household. The PRESYON study series showed a progressive rise in the prevalence of hypertension in the Philippines.12–15 Data control and validation in all PRESYON studies were strictly implemented. To ensure quality in data gathering and interview outcomes, there were three phases of data control and validation: Phase 1, editing of questionnaires for completeness and consistency; Phase 2, back-checking of completed interviews; and Phase 3, daily tabulation and summary of implementation by interviewers.12–15

Increasing Prevalence of Hypertension in the Philippines

The PHA–Council on Hypertension has determined that the prevalence of hypertension in the Philippines is increasing (Figure 1). The first study (PRESYON 1) was conducted in 1998 and found a prevalence of hypertension of 22%.12 In PRESYON 2, conducted in 2007, the prevalence of hypertension was 21%;13 in 2013 (PRESYON 3), this had increased to 28%14 and, in 2021 (PRESYON 4), this had increased further to 37%.15 In PRESYON 4, Grade 1 hypertension was predominant (34%), with rates of Grade 2 and Grade 3 hypertension being 25% and 15%, respectively.15 Also of note in PRESYON 4 was the 19% prevalence of high normal blood pressure among the surveyed population (130–139/85–89 mmHg) and a 26% prevalence of isolated systolic hypertension.14 In all four PRESYON studies, the sex distribution of hypertension was equal (males, 50%; females, 50%).12–15

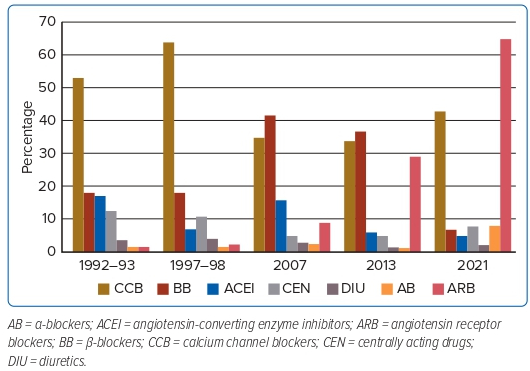

Important highlights from PRESYON 1, 2 and 3 include details regarding the rates of drug treatment, treatment adherence, blood pressure control and the risk profile of Filipinos with hypertension.12–14 In a 1992 survey and in PRESYON 1 (1997–98), calcium channel blockers were the most commonly used antihypertensive drugs in the Philippines (Figure 2).12,15 However, in PRESYON 2 (2007) and PRESYON 3 (2013), beta-blockers were the most commonly used drugs for the treatment of hypertension.13,14 In the most recent survey (PRESYON 4; 2021), the most widely used antihypertensive drugs were angiotensin receptor blockers.15 Other studies on the prevalence of hypertension in the Philippines conducted by other groups reported prevalence rates consistent with those reported in the PRESYON studies.16–18

Risk Profile of Filipinos With Hypertension

Because of the continuous rise in the prevalence of hypertension and the persistence of hypertension as the most common risk factor among patients hospitalised for any CVD, the Council on Hypertension of the PHA saw the need to assess the risk profile of hypertensive Filipinos. Hence, the Council monitored not only the rates of blood pressure control, treatment and compliance, but also the risk profile of hypertensive Filipinos surveyed, and followed trends throughout the series of PRESYON studies.

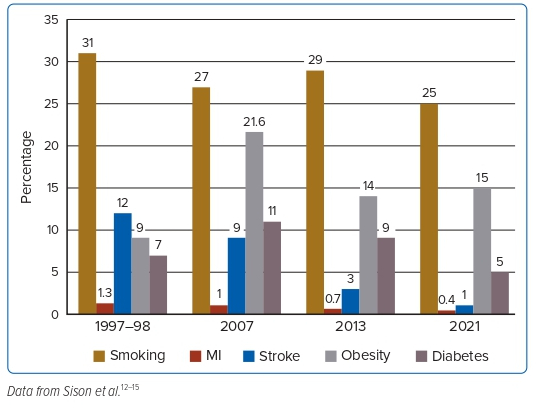

The series of studies into hypertension in the Philippines conducted over the past three decades included an assessment of risk factors, such as obesity, smoking and diabetes, as well as comorbidities such as MI and stroke. The hypertension surveys conducted by the PHA from 1997 (PRESYON 1) to 2021 (PRESYON 4) showed a decrease in smoking rates (from 31% to 25%), an increase in obesity (from 9% to 15%), a decrease in diabetes (from 7% to 5%), a decrease in MI (from 1.3% to 0.4%) and a decrease in stroke (from 12% to 1%; Figure 3).12,15

Analysis of the Latest Study (PRESYON 4)

The increase in the prevalence of hypertension from PRESYON 3 (2013) to PRESYON 4 (2021) was relatively larger (32% increase) compared with previous PRESYON studies, in which the rate of increase ranged from 3% to 4%.12,13,15

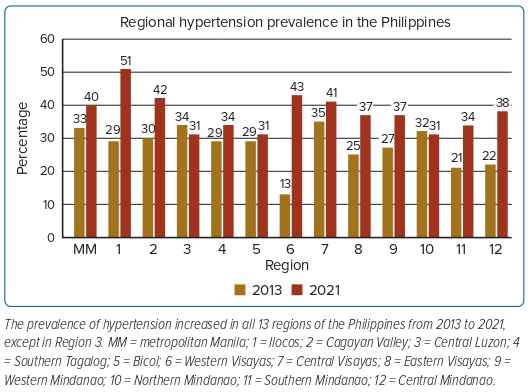

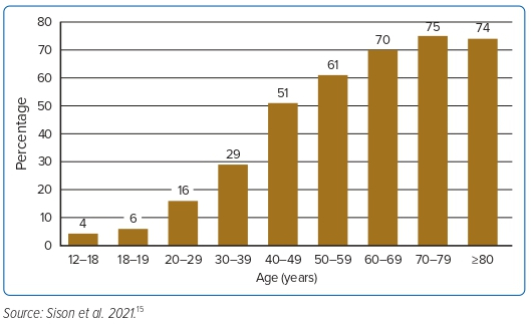

In PRESYON 4, the prevalence of hypertension increased in 12 of 13 regions in the Philippines (Figure 4). The rate of awareness of hypertension in PRESYON 4 was 19%, whereas unawareness of having hypertension was 18%.15 These rates were relatively better than those in PRESYON 3 (2013), in which the rates of awareness and unawareness were 15% and 8%, respectively.15 Interestingly, in PRESYON 4 the prevalence of hypertension among the elderly population (age ≥60 years) was 72%.15 This is not unexpected because hypertension is correlated with age. In PRESYON 4, awareness was high at 71%, while unawareness was only 29%.15 Presumably, the high prevalence of hypertension among the elderly and the high levels of awareness of hypertension reflect the fact that more elderly hypertensive individuals have had their diagnosis confirmed, undergone work-ups, are on maintenance antihypertensive drugs and are seeing their doctors regularly. If the rate of awareness is broken down according to age group, the rates of awareness (versus unawareness) start to increase at age 50–59 years (39% versus 21% unaware), further increasing at age 60–69 years (48% versus 21%), 70–79 years (61% versus 17%) and ≥80 years (45% versus 29%).15

Looking at the prevalence of hypertension according to age group reveals that it starts to increase at 51% at 40 years of age, showing incremental increases with increasing age and plateauing at ≥70 years of age.15 Note, however, that the prevalence of hypertension in the group aged 30–39 years has increased significantly by almost fivefold compared with that in individuals aged 18 years (Figure 5).15

Another interesting observation in PRESYON 4 is the apparent shift in the prevalence of hypertension from urban to rural areas.15 Compared with PRESYON 3 (2013), in PRESYON 4 there was a slight decrease in the prevalence of hypertension in urban areas (from 53% in 2013 to 51% in 2021), but a slight increase in rural areas (from 47% in 2013 to 49% in 2021). This may reflect a gradual ‘urbanisation’ of the rural areas (Supplementary Material Figure 1).

Treatment Compliance Profile and Control Rate

In PRESYON 4, 68% of the hypertensive population is on some form of antihypertensive medication.15 Among these individuals, the blood pressure control rate is 38%.15 Considering all hypertensive individuals, regardless of treatment or not with antihypertensive medications, the blood pressure control rate was only 37%.15 Compared with PRESYON 1, 2 and 3, in which the blood pressure control rates were 10%, 13% and 20%, respectively, PRESYON 4 only showed a slight improvement.12–15 The rate of compliance with antihypertensive medication in PRESYON 4 was 86%.15 However, among medication-compliant individuals, the blood pressure control rate was only 39%.15 This can be explained, in part, by the fact that 79% of those taking antihypertensive medications are on monotherapy. It has been proven that in order to achieve target blood pressure control, more than two antihypertensive drugs are needed.19–22

In PRESYON 4, blood pressure monitoring was most commonly performed in community health centres (44%), followed by home blood pressure monitoring (23%), clinic/office monitoring (15%) and hospital/outpatient monitoring (8%).15 Among those who performed home blood pressure monitoring, 44% used a brachial oscillometric (digital) blood pressure gadget, 15% used a digital wrist-type monitor, 18% used an aneroid monitor and 8% used a mercury sphygmomanometer.15

Anthropometric Profile of Hypertensive Filipinos

In PRESYON 4, most of those with hypertension in the survey were obese, with a mean BMI of 26.4 kg/m2 and a waist circumference of 90 cm.15 Comparing the anthropometric features of the hypertensive versus non-hypertensive population, hypertensive individuals had higher mean BMI (26.4 kg/m2 versus 24.2 kg/m2), were more likely to be overweight (BMI 25–29 kg/m2; 37% versus 28%) and were more likely to be obese (BMI ≥30 kg/m2; 21% versus 11%).15 The study also found a higher rate of central obesity among hypertensive than non-hypertensive individuals (34% versus 14%).15 Interestingly, the hypertensive population had a bigger mean left arm circumference (30.8 versus 29.1 cm; Supplementary Material Table 1).15 These left-arm measurements are reflective of the higher rate of overweight/obesity and central obesity among the hypertensive population. Similarly, these findings prove that the hypertension in this survey correlates well with known risk factors that predispose to cardiovascular risk, such as metabolic syndrome.

Implications of the PRESYON 4 Study

Based on the continuous increase in its prevalence and the poor blood pressure control rate despite high rates of compliance and treatment, hypertension remains a major problem in the Philippines in almost all regions of the country. The most recent survey (PRESYON 4) identified several factors hindering successful management of hypertension in the Philippines. One of these factors is the preponderance of monotherapy, which was also identified in earlier PRESYON studies starting in 1998 (PRESYON 1), despite the fact that, based on clinical trials, the use of more than two drugs is necessary to achieve target blood pressure control.6 This explains why, despite the high rate of treatment and compliance, the blood pressure control rate is still low in the Philippines. One may speculate that there is therapeutic inertia among physicians, and an important need to further educate them with regard to optimising blood pressure control, especially the use of drug combinations. Alternatively, there may be problems with drug availability or accessibility, particularly in remote areas of the country, where adequate services of the Department of Health are still lacking.

Another factor hindering the successful management of hypertension in the Philippines is the low rate of home blood pressure monitoring among hypertensive individuals. The importance of home blood pressure monitoring is to alert individuals of the need to see their doctor for adjustment or modification of their drugs to control their blood pressure. Drug combination for effective BP control is needed and should always be considered by their doctors.

The finding of a poorer risk profile among hypertensive individuals, particularly obesity, relating to a higher cardiovascular risk should alert not only these individuals, but also the physicians involved in their management of the need to encourage a healthy lifestyle, attain an ideal body weight, to eat a proper diet and to stop smoking.

The PHA is tasked with creating awareness of the importance of adequate management of hypertension in the Philippines among its members. This is important to create a multipronged approach for a more comprehensive strategy to control hypertension and lower cardiovascular risk. This should include launching programs for lay education using the PHA website, social media and traditional media (print, TV and broadcast platforms). The organisation should encourage its members to conduct year-round continuing medical education programs for healthcare providers and to collaborate with the government through the Department of Health to disseminate information emphasising the value of controlling hypertension and preventing cardiovascular complications in the Philippines.

Click here to view Supplementary Material

Clinical Perspective

- Based on the PRESYON study series, the prevalence of hypertension in the Philippines is increasing.

- Despite high rates of treatment and compliance, the blood pressure control rate remains low. Hypertensive individuals have poor risk profiles and have a high degree of unawareness of their condition. Monotherapy for hypertension has been predominant in all PRESYON studies conducted.

- The treatment strategy should focus more on drug combinations, improving poor risk profiles and enhancing lay education.