Growth differentiation factor-15 (GDF-15) is a member of the transforming growth factor β cytokine superfamily. It is weakly expressed in healthy individuals, with normal values in healthy elderly people reported to be <1,200 ng/l.1,2 Pregnancy is an exception, as there are high concentrations of GDF-15 in placental tissues under physiological conditions.3

The expression of GDF-15 is stress-responsive and rises sharply in conditions of pathological or environmental stress, such as hypoxia, oxidative stress, inflammation, tissue injury and remodelling.4,5 Conditions or disease states such as older age, smoking, diabetes, acute or chronic inflammation, chronic kidney disease (CKD), anaemia and bleeding, vascular disease, solid cancers and terminal illness are associated with elevated GDF-15 concentrations.4

Concentrations of GDF-15 increase across the cardiovascular disease continuum, including coronary artery disease, AF and acute and chronic heart failure (HF), and reflect overall disease burden, severity and adverse outcomes independent of other established risk factors.4,6–16 Although the pathophysiology of GDF-15 is not well understood, it could represent an integrated biomarker of multiple comorbidities rather than a specific reflection of cardiovascular health linked by common pathways, such as inflammation, endothelial dysfunction and oxidative stress.17

In HF, N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP), which is generally regarded as the gold standard biomarker, is elevated in response to myocardial stretch. Conversely, increases in GDF-15 reflect both cardiac and extracardiac abnormalities, capturing different aspects of the HF pathological spectrum.18

The HF population in the Asia-Pacific region is largely unrepresented in previous GDF-15 trials. It is unknown with the same findings described above can be applied to this population, and this provided the rationale for the present study.

Methods

This was a prospective observational study with the aim of determining, in a population of chronic HF patients with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF): the relationship between the novel biomarker GDF-15 and clinical and biochemical parameters; and the role of GDF-15 in predicting the outcome of all-cause mortality.

Patient Population

This study recruited patients with chronic HF with reduced LVEF, defined as LVEF ≤40%, attending the HF Clinic in the Sarawak Heart Center between October 2020 and April 2021. Patients with a previous diagnosis of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction and a documented LVEF ≤40%, but with an improved or recovered ejection fraction, were included in the study. Patients with recent (HHF) within 30 days) hospitalisation for heart failure (HHF) or acute coronary syndrome within 30 days were excluded.

Procedures and Follow-up

At study entry, blood samples were obtained for determination of NT-proBNP, GDF-15 and creatinine concentrations. Clinical information, such as blood pressure, heart rate, height and weight, was recorded and patient data, such as New York Heart Association (NYHA) class and HF medications, were collected. The LVEF was derived from echocardiography and measured using the modified Simpson method. The LVEF from echocardiographic studies within 3 months of study entry was accepted. The Meta-Analysis Global Group In Chronic (MAGGIC) risk score was calculated.19,20 Patients were subsequently followed up in the HF Clinic as per routine clinical practice. The frequency of patient visits was at the discretion of the attending cardiologist according to clinical need. The interval between clinic visits was no longer than 3 months. Any mortality event during the follow-up period was recorded.

Definitions

As proposed by Felker et al., ischaemic cardiomyopathy was defined as HF associated with a history of MI or revascularisation (coronary artery bypass grafting or percutaneous coronary intervention); ≥75% stenosis of the left main or proximal left anterior descending artery; and ≥75% stenosis of two or more epicardial vessels.21

In addition, patients with cardiac MRI demonstrating infarction of a degree and in a coronary territory deemed substantial to account for the degree of left ventricular systolic dysfunction not otherwise attributable to another identifiable cause by the investigators were also classified as having ischaemic cardiomyopathy despite their coronary angiography findings not meeting the criteria listed above.

CKD was defined as an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of <60 ml/min/1.73 m2. The eGFR was calculated using the CKD Epidemiology Collaboration creatinine equation (2021).22

The duration of HF was defined as the time between the first diagnosis of heart failure and study entry, and was expressed in months. Prior HHF was defined as any HHF before study entry.

Laboratory Procedures

Blood samples for determination of GDF-15 and NT-proBNP were drawn and the serum concentrations were measured using electrochemiluminescence on a cobas e411 analyser using the sandwich testing principle (Roche Diagnostics).

Statistical Analysis

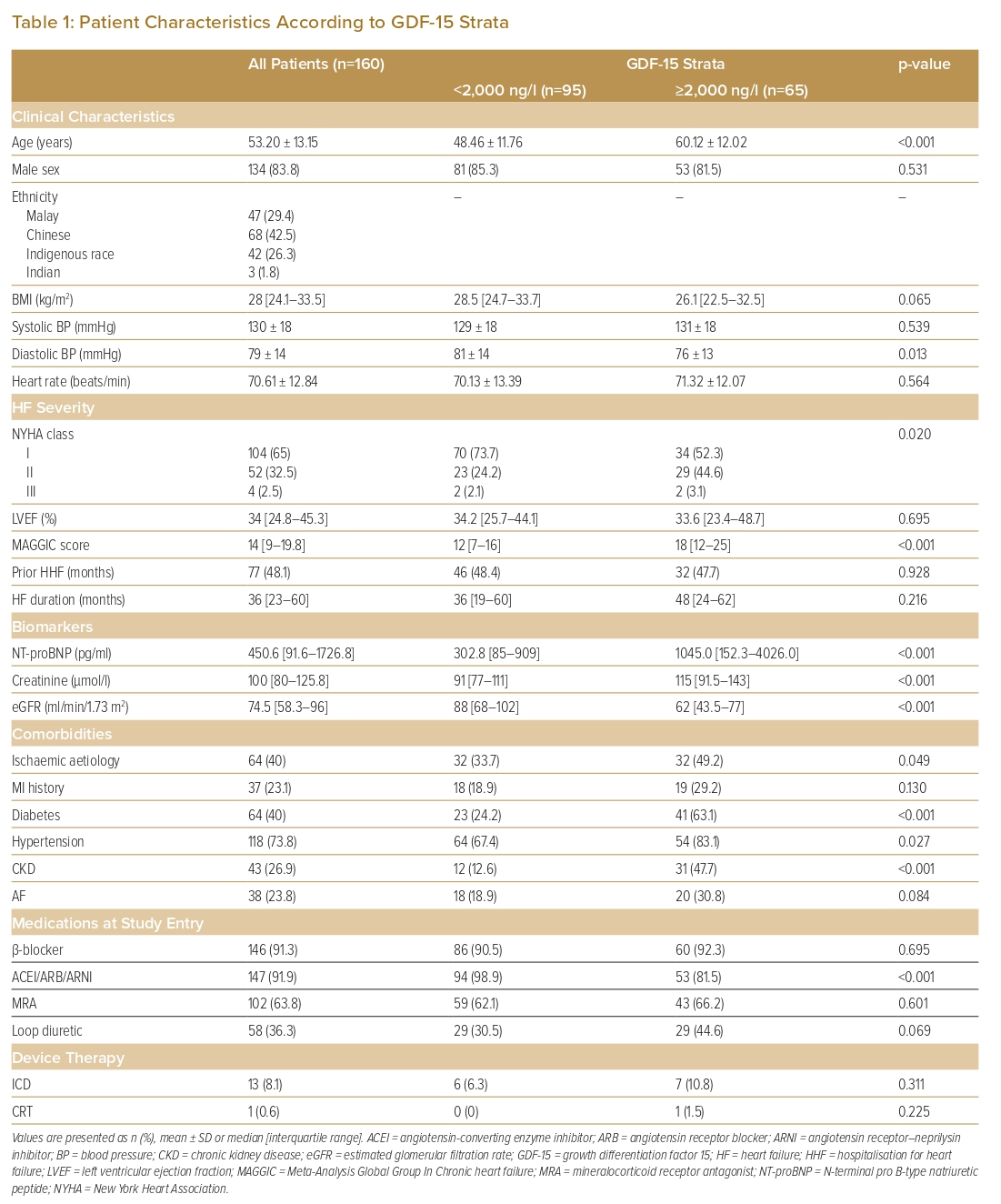

Categorical variables are expressed as absolute numbers and percentages, whereas continuous variables are presented as the mean ± SD in the case of a normal distribution or as the median and interquartile range (IQR) for variables with a skewed distribution. Continuous variables were tested for normal distribution using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Baseline characteristics are presented in Table 1 according to GDF-15 strata (<2,000 and ≥2,000 ng/l). Relationships between the GDF-15 strata and patient characteristics were compared using the χ2 test for categorical variables, one-way ANOVA for normally distributed continuous variables and the Kruskal–Wallis H-test for skewed continuous variables.

Multilinear regression was used to assess the association of GDF-15 and selected clinical and biochemical parameters. Variables that were not normally distributed were transformed into natural logarithms (ln). A backward selection method was used.

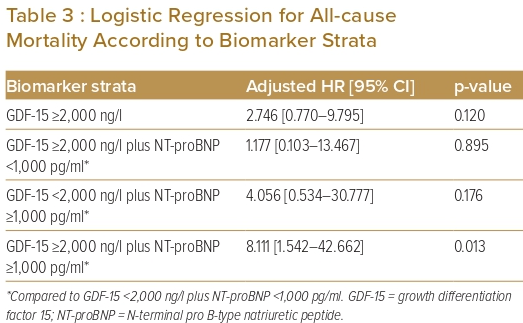

Binary logistic regression was used to assess the association of GDF-15 with the outcome of all-cause mortality. Analyses were performed with GDF-15 strata (<2,000 and ≥2,000 ng/l), as well as pooled strata of: GDF-15 <2,000 ng/l plus NT-proBNP<1,000 pg/ml; GDF-15 >2,000 ng/l plus NT-proBNP <1,000 pg/ml; GDF-15 <2,000 ng/l plus NT-proBNP >1,000 pg/ml; and GDF-15 >2,000 ng/l plus NT-proBNP >1,000 pg/ml. The cut-off values of 2,000 ng/l GDF-15 and 1,000 pg/ml NT-proBNP represent prognostic thresholds and have been described in prior studies.7,8

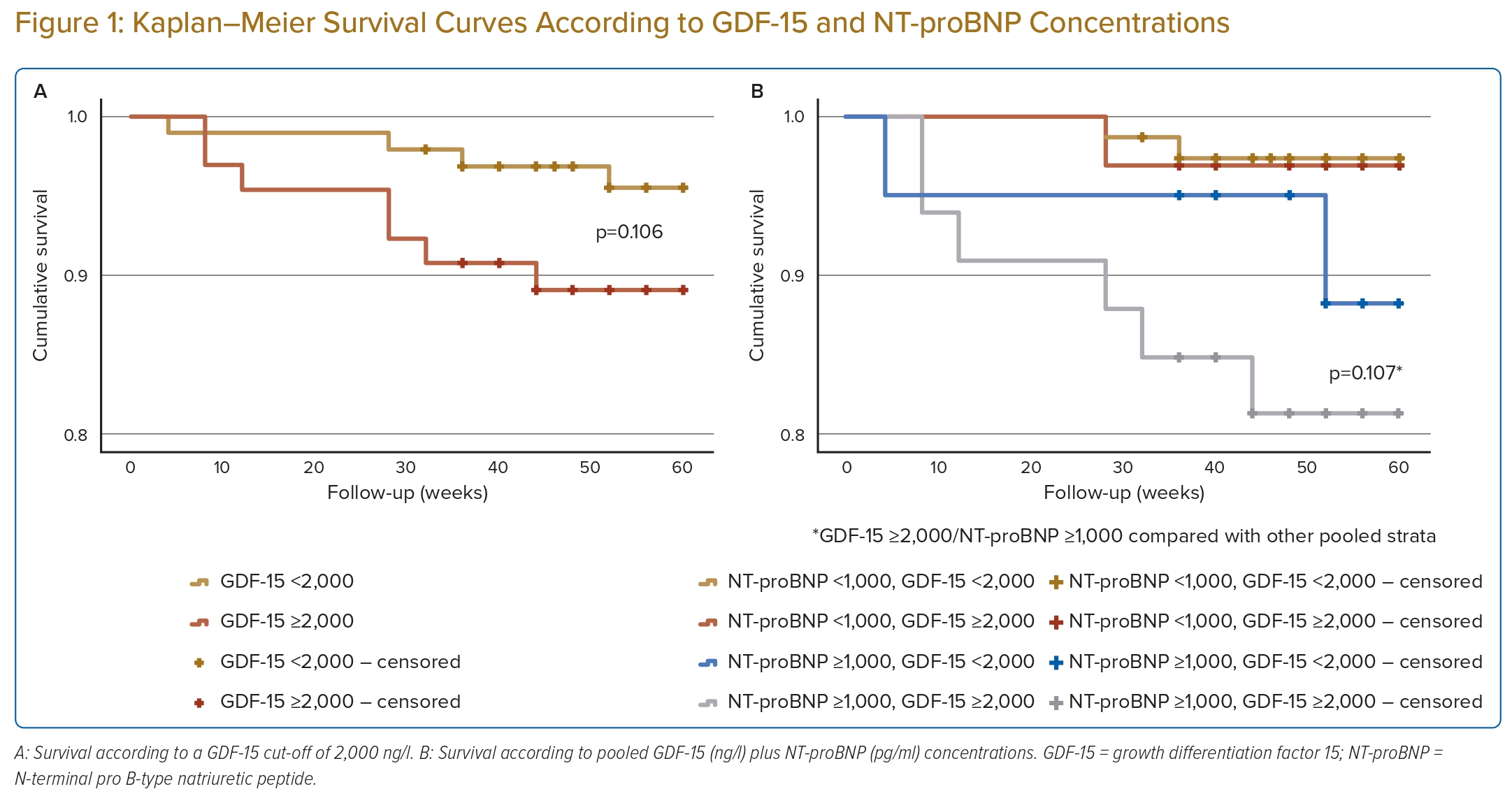

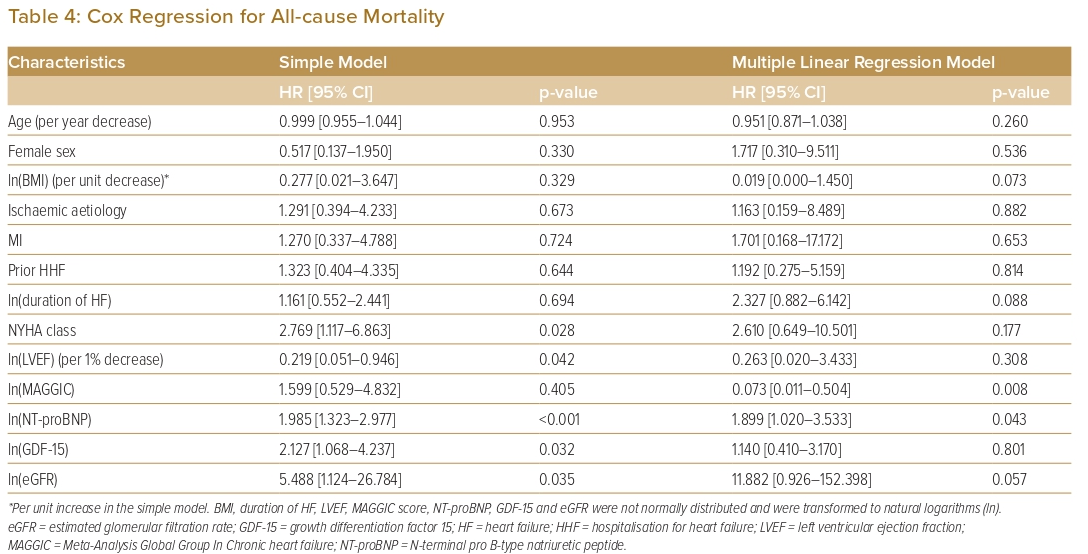

Kaplan–Meier plots were used to estimate the time-to-event for all-cause death for GDF-15 stratified as <2,000 and ≥2,000 ng/l, as well as for the pooled GDF-15 and NT-proBNP strata described above. Cox regression analysis was used to explore independent predictors of all-cause mortality. Analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Version 28.0.1.0. In all cases, p<0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Baseline Characteristics

In all, 160 patients entered the study between October 2020 and April 2021. Patient status was recorded up until January 2022. The median length of follow-up was 56 weeks (IQR 48–60 weeks). At the end of follow-up, 11 (6.9%) patients were dead.

Patient characteristics are presented in Table 1. Overall, the median GDF-15 concentration was 1715.0 ng/l (IQR 986.3–2,881.3 ng/l) and the median NT-proBNP concentration was 450.6 pg/ml (IQR 91.6–1,726.8 pg/ml). Most patients were male (83.8%). The mean age of the cohort was 53.2 ± 13.2 years, and 65% of the patients were in NYHA class I.

Compared with the GDF-15 <2,000 ng/l group, the GDF-15 ≥2,000 ng/l group was significantly older (mean age 60.1 ± 12.0 years; p<0.001), had more severe HF, was more symptomatic (p=0.020), and had a higher median NT-proBNP concentration (p<0.001) and a higher MAGGIC risk score (p<0.001). The median LVEF for the entire cohort was 34% (IQR 24.8–45.3%). There was no statistically significant difference in LVEF, the duration of HF or a history of HHF between the GDF-15 <2,000 and ≥2,000 ng/l groups.

Forty per cent of patients had HF of ischaemic aetiology, and 23.1% had a history of MI. The GDF ≥2,000 ng/l group had a higher percentage of patients with ischaemic HF and a history of MI compared with the GDF-15 <2,000 ng/l group, but the difference was only significant for ischaemic HF (p=0.049).

Comorbidities in the entire cohort included diabetes (40%), hypertension (73.8%), CKD (26.9%) and AF (23.8%). Of these comorbidities, diabetes, hypertension and CKD were more prevalent in the GDF-15 ≥2,000 than <2,000 ng/l group (p<0.001, p=0.027 and p<0.001, respectively).

At study entry, there was a high prevalence of β-blocker and renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS) inhibitor therapies (91.3% and 91.9%, respectively); 63.8% of patients were on mineralocorticoid antagonists (MRA)s and 36.3% were on loop diuretic. Of those on RAAS inhibitors, 40% were on an angiotensin receptor–neprilysin inhibitor (ARNI). There were fewer patients on RAAS inhibitors in the GDF-15 ≥2,000 ng/l group (p<0.001).

HF device therapies were infrequent, with only 8.1% and 0.6% of the overall cohort having received an ICD and CRT, respectively.

Association of Growth Differentiation Factor 15 with Other Clinical and Biomarker Prognosticators

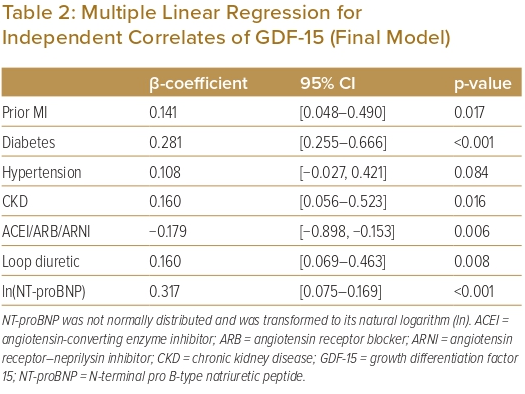

In the multilinear regression analysis using a backward selection method, the following variables were tested for an association with GDF-15 (expressed as ln(GDF-15) in the analysis): age, male sex, ln(body mass index), systolic blood pressure, heart rate, NYHA class, ln(LVEF), ln(NT-proBNP), ln(eGFR), ischaemic aetiology, a history of MI, ln(HF duration), diabetes, hypertension, AF, CKD, β-blocker therapy, RAAS inhibitor therapy, MRA therapy and loop diuretic therapy. These variables were checked for multicollinearity and there was none. In the final model (Table 2), the predictors significantly associated with GDF-15 were a history of MI, diabetes, CKD, therapy with an RAAS inhibitor and loop diuretics and NT-proBNP. Of these, a history of MI (p=0.017), diabetes (p<0.001), CKD (p=0.016), therapy with diuretics (0.008) and NT-proBNP (p<0.001) were positively correlated with GDF-15. Conversely, therapy with an RAAS inhibitor (p=0.006) was negatively correlated with GDF-15.

Association of Growth Differentiation Factor 15 With All-cause Mortality

There were more all-cause deaths in the GDF-15 ≥2,000 ng/l group than in the GDF-15 <2,000 ng/l group (10.8% versus 4.2%; p=0.107). When GDF-15 was pooled with NT-proBNP, the group GDF-15 ≥2,000 ng/l plus NT-proBNP ≥1,000 pg/ml group had the highest percentage of all-cause deaths (18.2% versus 2.7% in the GDF-15 <2,000 ng/l plus NT-proBNP <1,000 pg/ml group; 3.1% in the GDF-15 ≥2,000 ng/l plus NT-proBNP <1,000 pg/ml group; and 10% in the GDF-15 <2,000 ng/l plus NT-proBNP >1,000 pg/ml group). This difference was statistically significant (p=0.017).

In the logistic regression analysis, GDF-15 ≥2,000 ng/l was positively correlated with all-cause mortality. However, the correlation was not significant (p=0.120). When both GDF-15 and NT-proBNP were considered together, GDF-15 ≥2,000 ng/l pooled with NT-proBNP ≥1,000 pg/ml had the strongest correlation with all-cause mortality compared with GDF-15 <2,000 ng/l plus NT-proBNP <1,000 pg/ml (p=0.013; Table 3). The Kaplan–Meier survival curves for unadjusted all-cause mortality are shown in Figure 1.

To estimate the independent effect of each variable on the outcome of all-cause death, Cox regression analysis was performed. Only the MAGGIC risk score and NT-proBNP concentration were predictive of the outcome at 60 weeks (Table 4)

Discussion

In this study, the GDF-15 concentration was significantly and positively correlated with NT-proBNP concentration and comorbidities, such as diabetes, CKD and MI. Patients with increased GDF-15 concentrations were also significantly less likely to be on RAAS inhibitor therapy, but more likely to be on loop diuretic therapy. The link between diabetes or CKD and oxidative stress has been described, and our observation supports the expression of GDF-15 being stress-responsive.23–26 GDF-15 is also expressed in infarcted myocytes and has been shown to be higher in a cohort of patients presenting with acute MI who had previous acute MI compared with those who did not.27 In one study, a higher GDF-15 concentration was associated with lower use of RAAS inhibitor and β-blocker therapies.8 In that study, the prevalence of β-blocker use was much lower compared with that in the present study (58.6% versus 91.3%), although how this relates to the respective findings is uncertain.

Numerous studies including heterogeneous groups of HF patients have shown GDF-15 to be an independent predictor of mortality.7,8,28–32 The study populations have ranged from acute to chronic HR, with either reduced or preserved LVEF or both. In contrast, the present study recruited only patients with chronic HF with reduced LVEF. Compared with previous studies, the present study cohort was younger and generally well-optimised on medical therapy, had a lower median NT-proBNP concentration and a lower prevalence of ischaemic cardiomyopathy. The most striking difference was the high prevalence of asymptomatic patients (65% in NYHA class I). Other studies have recruited only symptomatic patients in NYHA class II–IV. Another notable difference is the use of ARNI. Previous studies included patients whose RAAS inhibitor therapy consisted of either an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin II receptor blocker.7,8,28–32 In the present study, 40% of the cohort were on ARNI.

These differences could explain the lack of a significant association between the previously described cut-off value of GDF-15 ≥2,000 ng/l and all-cause mortality.7,8 When considered together with NT-proBNP, the group with the highest level of each biomarker (GDF-15 ≥2,000 ng/l and NT-proBNP ≥1,000 pg/ml) had a significantly higher all-cause mortality rate than the group with the lowest biomarker levels (GDF-15 <2,000 ng/l and NT-proBNP <1,000 pg/ml). This could suggest that, in well-managed, largely asymptomatic patients, a different cut-off value of GDF-15 or a dual-biomarker strategy should be considered.

The MAGGIC risk score was developed from a large patient database (>39,000 patients from 30 cohort studies) to predict mortality in patients with HF, and has been externally validated.19,20 NT-proBNP has been shown to be an independent predictor of mortality in a population of chronic and stable HF patients.33 In our study, both MAGGIC risk score and NT-proBNP were independently predictive of all-cause mortality, an observation consistent with previous findings. In the univariate model, elevated GDF-15 was significantly associated with all-cause mortality, but in the multivariate model it was not. It is uncertain whether the interaction between the different parameters contributed to this finding, but the covariates were checked for multicollinearity, and none was found.

The limitations of this study are its small sample size and that it was a single-centre study.

Conclusion

In conclusion, in our cohort of younger, well-managed and mostly asymptomatic patients with chronic HF with reduced LVEF, GDF-15 did not independently predict all-cause mortality, and the prognostic cut-off of GDF-15 ≥2,000 ng/l was not significantly associated with a higher all-cause mortality at 60 weeks. In this cohort, NT-proBNP and MAGGIC risk score were independent predictors of all-cause mortality. More studies are needed to re-explore the prognostic cut-off value of GDF-15 and its role in risk prediction in contemporary HF patients exposed to new HF therapies, such as ARNI and sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors.

Clinical Perspective

- This study cohort differed from those in previous studies of GDF-15 in terms of age (younger), symptoms (more NYHA class I) and medical therapy (ARNI).

- The previously described GDF-15 prognostic cut-off value of ≥2,000 ng/l was not significantly associated with all-cause mortality at 60 weeks.

- GDF-15 did not independently predict all-cause mortality.

- Findings from previous GDF-15 in HF studies may not be generalisable to all HF patients.

Comments