In the Asia-Pacific region, acute coronary syndrome (ACS) remains a major cause of death and disability, with in-hospital mortality typically exceeding 5%.1 Furthermore, regional data showed that 10–15% of patients with acute MI (AMI) develop cardiogenic shock (CS), which was associated with an in-hospital mortality rate exceeding 30% and a 30-day mortality rate exceeding 40%.2,3

There is substantial heterogeneity in the management of ACS – including the management of CS – in the Asia-Pacific region; this heterogeneity is greater than in health systems in Western Europe or the US.1 The heterogeneity may be driven by several factors, including the lack of consensus on the optimal management of CS in the Asia-Pacific region. This lack of consensus may, in turn, be because of the paucity of clinical evidence generated from the region and differences in the availability of healthcare technologies and resources.

Given these challenges, there is a need for a unified but simple and practical approach to the management of AMI-CS to guide practitioners in the region. Hence, the Asian Pacific Society of Cardiology (APSC) developed these consensus recommendations to guide cardiologists and internal medicine specialists practising cardiology in the diagnosis and management of AMI-CS.

Methods

The APSC convened an expert consensus panel to review the literature on the diagnosis and management of AMI-CS, discuss gaps in current management, determine areas where further guidance is needed, and develop consensus recommendations on the diagnosis, assessment and management of AMI-CS. The 21 experts on the panel are members of the APSC who were nominated by national societies and endorsed by the APSC consensus board or invited international experts.

After a comprehensive literature search, selected applicable articles were reviewed and appraised using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation system.4 Based on this system, the levels of evidence were designated as follows:

- High (authors have high confidence that the true effect is similar to the estimated effect).

- Moderate (authors believe that the true effect is probably close to the estimated effect).

- Low (true effect might be markedly different from the estimated effect).

- Very low (true effect is probably markedly different from the estimated effect).

As indicated in these levels, the authors adjusted the level of evidence if the estimated effect, when applied in the Asia-Pacific region, may differ from the published evidence because of various factors such as ethnicity, cultural differences and/or healthcare systems and resources.

The available evidence was discussed during a virtual consensus meeting in October 2022. The consensus recommendations were then developed during the first meeting and were finalised during smaller, pocket virtual meetings held in January 2023. The final consensus statements were then put to an online vote, with each recommendation being voted on by each panel member using a three-point scale (i.e., agree, neutral or disagree). Consensus was reached when 80% of votes for a recommendation were ‘agree’ or ‘neutral’. In the case of non-consensus, the recommendations were further discussed using email communication then revised accordingly until the criteria for consensus were fulfilled.

Consensus Recommendations

Diagnosis, Assessment and Classification of Acute MI-Cardiogenic Shock

Statement 1. Immediate point-of-care echocardiography should be considered to assess ventricular and valvular functions, loading conditions and to detect mechanical complications. However, this should not delay reperfusion.

Level of evidence: Moderate.

Level of consensus: 90.5% agree; 0% neutral; 9.5% disagree.

Statement 2. Haemodynamic assessment of left ventricular enddiastolic pressure (LVEDP) may be considered for guiding therapy. It should not delay reperfusion.

Level of evidence: Low.

Level of consensus: 82.6% agree; 8.7% neutral; 8.7% disagree.

Statement 3. Haemodynamic assessment with pulmonary artery catheterisation (PAC) may be considered for guiding therapy. It should not delay reperfusion.

Level of evidence: Low.

Level of consensus: 87.0% agree; 8.7% neutral; 4.3% disagree.

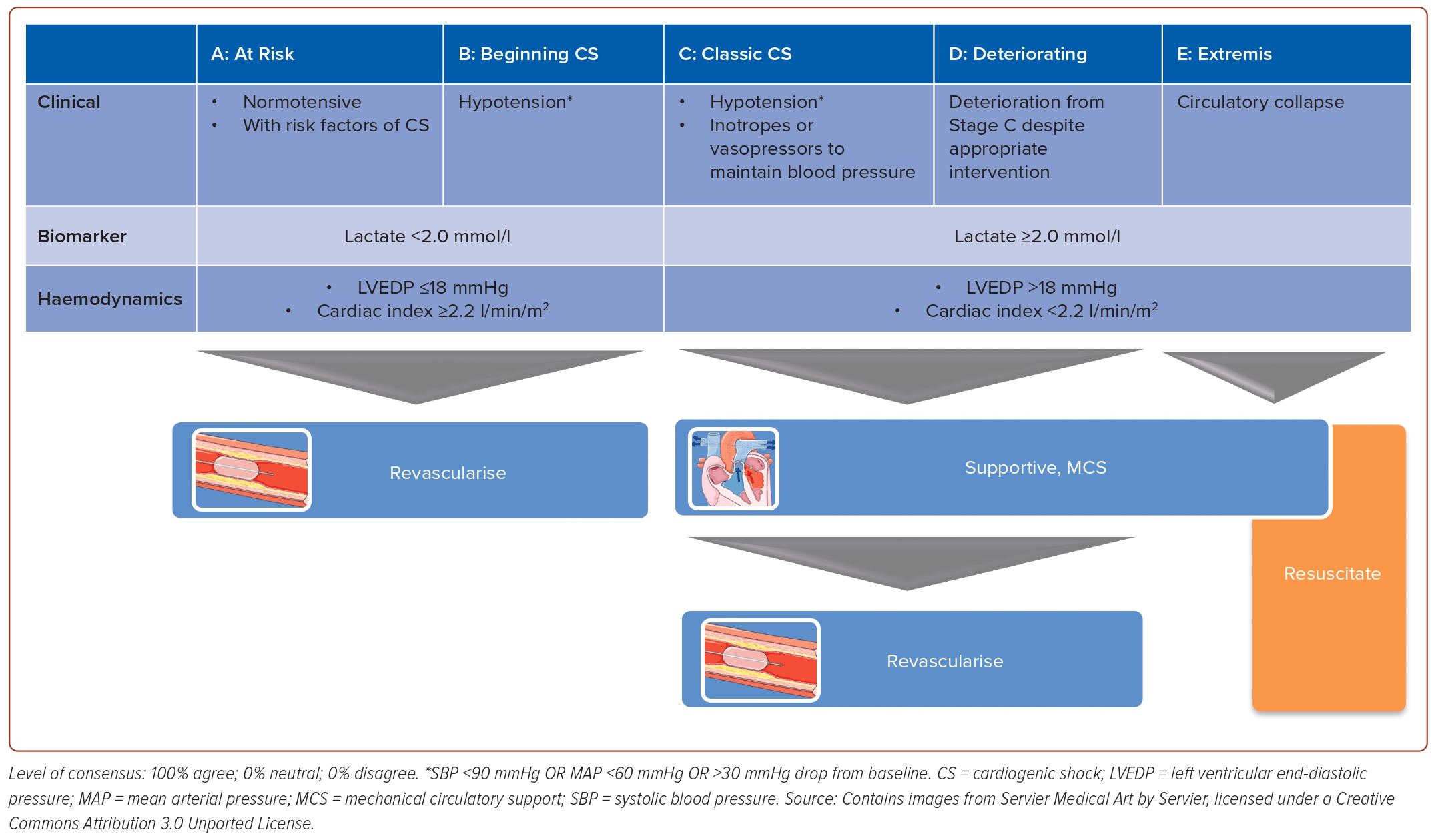

Statement 4. AMI patients with hypotension but with blood lactate <2.0 mmol/l, LVEDP ≤18 mmHg and cardiac index ≥2.2 l/min/m2 should be classified as being in Stage B CS.

Level of evidence: Moderate.

Level of consensus: 100% agree; 0% neutral; 0% disagree.

Statement 5. AMI patients who require the use of inotropes/ vasopressors to prevent hypotension should be classified as being in Stage C CS.

Level of evidence: Very low.

Level of consensus: 91.4% agree; 4.3% neutral; 4.3% disagree.

Statement 6. AMI patients with hypotension and with blood lactate ≥2.0 mmol/l, LVEDP >18 mmHg or cardiac index <2.2 l/min/m2 should be classified as being in Stage C CS.

Level of evidence: Very low.

Level of consensus: 100% agree; 0% neutral; 0% disagree.

During the consensus meeting, the panel agreed to base the classification of AMI-CS on the 2019 Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions (SCAI) clinical expert consensus statement on the classification of CS, with some simplifications (Figure 1).5 The panel also defines hypotension as a systolic blood pressure <90 mmHg. While the 2019 SCAI classification indicated the use of several biochemical and haemodynamic parameters, the panel decided to select only a few parameters that are readily available in most centres in the region and could provide the most distinguishing measures to classify the stage of shock. The chosen parameters were blood lactate, LVEDP and cardiac index. Other parameters of cardiac performance (e.g. cardiac power output) were considered but thought to be too complex for routine rapid decision-making. While lactate levels can be easily measured from blood, LVEDP is measured through catheterisation of either the left ventricle (direct measurement) or the pulmonary artery (indirectly via pulmonary capillary wedge pressure). The recently published SCAI Shock Classification update incorporated data from the retrospective and prospective validations of the SCAI Shock Classification that provided data on a variety of definitions used for classification.6 In addition, a recent paper from the CS Working Group provided strong supporting data from the SCAI Shock Classification definitions.7 Based on these parameters, the panel voted to define AMI with hypotension but with blood lactate <2.0 mmol/l, LVEDP ≤18 mmHg and cardiac index ≥2.2 l/min/m2 as Stage B CS, whereas AMI patients with hypotension and with blood lactate ≥2.0 mmol/l, LVEDP >18 mmHg or cardiac index <2.2 l/min/m2 should be classified as being in Stage C CS. AMI patients who require the use of inotropes or vasopressors to maintain blood pressure should also be classified as being in Stage C CS. A few panellists also opined that patients who need mechanical circulatory support (MCS) to maintain blood pressure should also be classified as Stage C.

The echocardiogram is considered one of the most useful tools to assess CS.8–11 Aside from providing information on cardiac output, which is needed to determine the cardiac index, this modality provides information regarding ventricular function (e.g. reduction in left ventricular [LV] function or right ventricular [RV] infarction), valvular function (e.g. acute severe mitral regurgitation), loading conditions and mechanical complications of AMI (e.g. LV free wall rupture, ventricular septal rupture and papillary muscle rupture). Furthermore, normal LV and RV systolic function, normal cardiac chamber dimensions, absence of any significant valvular pathology and absence of any pericardial effusion may rule out a cardiac cause of shock.8–11

Haemodynamic assessment via PAC is also suggested in patients with on-going AMI-CS. PAC provides important prognostic and predictive haemodynamic information, may distinguish right ventricular shock, as well as aids in the assessment of volume status and adequacy of resuscitation.8,9,12–14

Lastly, the authors emphasise that revascularisation provides the most clinical benefit in patients with AMI and the availability of point-of-care echocardiography and haemodynamic assessment may vary between centres. Hence, these diagnostic procedures should not delay revascularisation.8,9 In case diagnostic procedures are expected to cause delay, clinicians may rely initially on physical examination and bedside findings to aid in expediting decision-making.

Management of Acute MI-Cardiogenic Shock in Stage B

Statement 7. Immediate revascularisation is recommended for AMI patients with Stage B CS.

Level of evidence: Moderate.

Level of consensus: 100% agree; 0% neutral; 0% disagree.

Statement 8. The majority of patients only require revascularisation of the culprit lesion.

Level of evidence: Low.

Level of consensus: 78.3% agree; 17.4% neutral; 4.3% disagree.

Aside from demonstrating the classification of AMI-CS, Figure 1 also presents the general framework of management according to the stages of CS. In this framework, Stage B, which is considered ‘beginning’ CS or compensated shock, refers to a patient with clinical evidence of relative hypotension or tachycardia without hypoperfusion.

Early revascularisation is the standard of care in patients with AMI, which may be considered Stage A AMI-CS (‘at risk’). International guidelines also recommend early revascularisation in patients with CS complicating AMI, based on the results of the SHOCK trial.8,9,15–18 Based on the inclusion criteria, patients in this trial had Stage C or worse CS (Stage C, D or E). Early revascularisation is also recommended by international guidelines for patients on the less severe end of the spectrum, i.e. those with ACS who do not yet exhibit signs and symptoms of hypoperfusion.8,9,15,16,18 On the other hand, randomised controlled trial (RCT) data exclusively on AMI patients with Stage B CS are sparse, particularly for non-ST elevation MI. Nonetheless, the expert panel underscored that early revascularisation maximises and preserves myocardial function, which may prevent the worsening of Stage B CS. Hence, the expert panel recommended early revascularisation in Stage B patients.

Approximately 80% of patients with CS complicating AMI have multivessel coronary artery disease. In these patients, revascularisation may involve only the culprit lesion or all diseased lesions. On whether the majority of patients in Stage B AMI-CS would only require revascularisation of the culprit lesion, the level of consensus was lower (only 78.3% agreed, 4.3% disagreed and 17.4% voted neutral). One of the possible reasons for this is the uncertainty in the evidence specific to Stage B patients. The CULPRIT-SHOCK trial showed that culprit-lesion-only percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) was associated with a significant reduction in all-cause death or renal replacement therapy at the 30-day follow-up.19 This indicates that non-culprit lesions should not be routinely treated immediately and that the majority of immediate PCI should be limited to the culprit lesion only. A meta-analysis of 16 studies (n=75,431) also confirmed multivessel PCI in AMI patients with CS was associated with a higher risk of early mortality, stroke and renal replacement therapy.20 However, most patients in these trials exhibit hypoperfusion, suggesting that those in Stage B are underrepresented. Meta-analysis on AMI patients without overt CS, on the other hand, reported beneficial effects on all-cause and cardiovascular mortality with complete revascularisation.21 These considerations should be taken into account when deciding on the revascularisation strategy of AMI patients with Stage B CS.

Management of Acute MI-Cardiogenic Shock in Stage C or Worse

Statement 9. Patient stabilisation is recommended before revascularisation in AMI patients with Stage C CS or worse.

Level of evidence: Very low.

Level of consensus: 74.0% agree; 21.7% neutral; 4.3% disagree.

Statement 10. For patients in Stage C CS, ensuring adequate oxygenation should be considered before transfer to the cardiac catheterisation laboratory.

Level of evidence: Very low.

Level of consensus: 78.3% agree; 21.7% neutral; 0% disagree.

Statement 11. Haemodynamic assessment with PAC should be considered for guiding therapy in patients with Stage C and Stage D CS.

Level of evidence: Moderate.

Level of consensus: 95.7% agree; 0% neutral; 4.3% disagree.

Statement 12. Temporary MCS (e.g. intra-aortic balloon pump [IABP], Impella or venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation [VAECMO]) may be considered in AMI patients in Stage C and Stage D CS.

Level of evidence: Low.

Level of consensus: 95.7% agree; 4.3% neutral; 0% disagree.

Statement 13. The use of MCS for patients in Stage E CS is considered futile. VA-ECMO may be considered in highly selected patients based on clinical imperatives.

Level of evidence: Low.

Level of consensus: 78.3% agree; 13.0% neutral; 8.7% disagree.

Statement 14. For patients in Stage C or Stage D, PCI (over emergency coronary artery bypass grafting) may be considered as the mode of revascularisation.

Level of evidence: Low.

Level of consensus: 91.3% agree; 8.7% neutral; 0% disagree.

The panel voted on whether patient stabilisation should be recommended before revascularisation in AMI patients with Stage C CS or worse. As previously mentioned, the SHOCK trial showed that, compared with initial medical stabilisation, early revascularisation improved 6-month mortality rates but did not significantly improve the primary endpoint of 30-day mortality.17 However, this study was designed in the early 1990s and medical stabilisation was defined in the study as intensive medical therapy, which included thrombolytic therapy in 63% of patients.

In the context of these consensus statements, stabilisation pertains to the correction of hypotension and factors that contribute to CS, such as the correction of hypovolaemia or arrhythmia and the use of vasopressors, inotropes and even inodilators, phosphodiesterase III inhibitors, or MCS devices, as needed.8,9,14 Recognising that many patients in the region, especially those in developing countries, would need to be transported to a tertiary centre for PCI or coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), these factors should be addressed in patients with Stage C CS, who may rapidly deteriorate to worse stages, before revascularisation.

Nonetheless, the level of consensus on this statement was lower (74.0% agreed, 21.7% were neutral and 4.3% disagreed). Some of the expert panellists pointed out that these interventions may be performed during and not prior to revascularisation. Other panellists explained that stabilisation may not be possible in many patients if the occluded vessel is the cause of the haemodynamic deterioration. Hence, factors such as the specific clinical characteristics of the patient, the availability of healthcare resources and the capabilities of the management team should all be considered.

Stabilisation also includes ensuring adequate oxygenation and ventilation. In the acute setting, blood oxygen saturation of >90% is acceptable.8,9,14 Invasive forms of ventilation are required if non-invasive forms of oxygenation and ventilation are unable to achieve oxygen saturation targets. Low tidal volumes may be lung protective and may decrease the risk of right ventricular failure (acute cor pulmonale).14,22 Similarly to the statement on stabilisation prior to revascularisation, the level of consensus for this statement was lower (78.3% agree, 21.7% neutral, 0% disagree) because of similar arguments, specifically the capacity of most catheterisation laboratories to ensure oxygenation during revascularisation.

While RCTs have failed to show mortality benefits with the use of PAC in patients with CS, patients with AMI-CS are underrepresented in these studies.23–26 The authors recognise that AMI-CS is a distinct phenotype of CS, that may present with high or low filling pressure, higher oxygen delivery, lower oxygen–haemoglobin affinity and more severe metabolic acidosis compared with CS in end-stage heart failure.27 Furthermore, AMI-CS is associated with higher inpatient mortality compared with CS in end-stage heart failure.6–9,28 It is also associated with higher inpatient mortality compared with patients with acute on chronic heart failure-related CS even with similar haemodynamic characteristics.6–9,29 Hence, it is difficult to extrapolate the benefits of PAC on AMI-CS from the results of the aforementioned trials.27 Recent American Heart Association (AHA) consensus statements on CS and AMI-CS strongly support the use of PAC-demand haemodynamic data. Meanwhile, a study by the CS Working Group found that the use of complete PAC-derived haemodynamic data prior to MCS initiation in patients with advanced CS stages was associated with improved survival (p<0.001), including the subgroup of patients with AMI-CS.30 Another study found AMI patients with CS treated with MCS along with invasive haemodynamic monitoring with a PAC had improved survival rates versus controls (p<0.001).31

Similar to the recently released guidelines of the Association for Acute Cardiovascular Care, the panel recommended that MCS devices may be used to maintain aortic pressure and haemodynamic stability in patients with Stage C or worse AMI-CS, and offer potential advantages over vasopressor therapy, such as the provision of cardiovascular support without increasing (and possibly decreasing) myocardial oxygen demand, thus reducing the risk of further myocardial ischaemia. 8,9, 32–37 Registry data also suggests that early MCS device use is associated with improved survival rates.38,39 Hence, the panel voted that temporary MCS (e.g. IABP, Impella) or VA-ECMO may be considered in AMI patients in Stage C CS or worse.

The IABP is the most widely available, least expensive and most commonly used MCS across the Asia-Pacific region. In a position paper, Italy’s Associazione Nazionale dei Medici Cardiologi Ospedalieri (National Association of Hospital Cardiologists) issued a practical recommendation, acknowledging the aforementioned benefits of IABP, stating that non-routine IABP may be used in initial or impending CS (Stage B) or selected patients with Stage C or worse CS, especially if other forms of MCS are not available.40 However, some expert panellists have highlighted that IABP should not be routinely implemented as RCTs have not been able to show improved outcomes in patients with ST-elevation MI (STEMI) and CS without mechanical complications.8,9,15,41 The 2017 European Society of Cardiology guidelines noted that IABP may be considered for haemodynamic support in patients with severe mitral insufficiency or ventricular septal defect.15

The evidence supporting the use of other forms of left ventricular assist devices is also limited but European guidelines state that short-term MCS may be considered in STEMI patients with refractory shock while for non-ST-elevation ACS, short-term MCS may be considered in selected patients, depending on age, comorbidities, neurological function and severity of CS.15,16 The APSC statements take on a similar stance, recommending temporary MCS in Stage C or worse MCS as a form of rescue therapy to stabilise patients, reduce myocardial demand and aid in the recovery of myocardial function and preservation of organ perfusion. This is also consistent with the recent AHA Consensus Statements and American College of Cardiology/AHA Guidelines.8,9,18

The expert panel voted (78.3% agree, 13.0% neutral, 8.7% disagree) to consider the use of MCS in patients with Stage E AMI-CS as futile, in contrast to European recommendations that indicate VA-ECMO as an option.32 In an observational study on 81 consecutive patients with worsening CS requiring temporary MCS escalation (33% due to AMI), patients in Stage E shock were associated with 100% mortality.42 These generally poor outcomes on top of the high costs and level of expertise required for MCS, especially VA-ECMO, contribute to the differing recommendations of the expert panel. However, in another observational study on patients with acute STEMI who underwent primary PCI and had CS, VA-ECMO was associated with lower mortality rates in patients with profound shock.43 Other predictors of survival in these patients were successful reperfusion and the absence of advanced congestive heart failure. These findings suggest a possible role of VA-ECMO in carefully selected patients based on clinical imperatives. One panellist suggested that emergency VA-ECMO in Stage E CS may be considered for those presenting with intractable ventricular arrhythmias to enable revascularisation. A few panellists also noted that, while the initiation of VA-ECMO early may potentially prevent the progression to Stage E, the initiation of VA-ECMO when the patient is already in Stage E is challenging but possible and would require adjustments in treatment protocols.

Lastly, the panel voted that, for patients in Stage C or Stage D CS, PCI may be considered over emergency CABG as the mode of revascularisation. The panel recognised that RCT data in this subset of patients are scarce and observational studies report conflicting results. In a large US registry study on AMI patients with CS, CABG without PCI was associated with lower mortality than PCI without CABG.44 In contrast, subanalysis of the SHOCK trial found that survival rates were similar between emergency PCI and emergency CABG.45 The panel reported that, in most centres in the region, emergency PCI is more readily available compared with emergency CABG and may be considered in most patients without compromising the outcomes of patients with Stage C/D AMI-CS. In contrast, CABG remains a strategy to consider in patients with suitable anatomy, especially when successful PCI is unlikely.46

Statements on the Approach to the Management of Acute MI-Cardiogenic Shock

Statement 15. A multidisciplinary team approach is recommended in the management of patients with CS due to AMI.

Level of evidence: Moderate.

Level of consensus: 100% agree; 0% neutral; 0% disagree.

Statement 16. A protocolised treatment is recommended in the management of patients with CS due to AMI.

Level of evidence: Moderate.

Level of consensus: 100% agree; 0% neutral; 0% disagree.

The expert panel recognised the high morbidity and mortality associated with AMI-CS, which would require the collective expertise of a multidisciplinary team and a systematic approach to care.8,9,47 Most of the prospective data on the clinical outcomes provided by multidisciplinary shock teams are from North American observational studies (e.g. National CS Initiative, Inova Heart and Vascular Institute CS Initiative, Utah Cardiac Recovery shock team and the University of Ottawa Heart Institute code shock team).8,9,36,48–50 These studies report high and/or improved historical survival rates in patients with CS. Shock teams also potentially help in decision-making, which may prevent delays in diagnosis and delivery of care. The panel also noted that a protocolised approach was a common strategy among these shock teams.8,9,36,48–50 Shock protocols enabled early identification of the appropriate plan of action and also improved quality measures, such as time to MCS without significantly delaying revascularisation.36,51

Limitations and Conclusion

The 16 statements presented in this paper aim to guide clinicians based on the most updated evidence and collective expert opinion from Asia-Pacific. However, given the varied clinical situations and healthcare resources present in the region, these recommendations should augment clinical judgement rather than replace it. The management of AMI-CS should be individualised, taking into account the patient’s clinical characteristics as well as patient and caregiver concerns and preferences. Clinicians should also be aware of the challenges that may limit the applicability of these consensus recommendations in the management of CS in their centre, such as the access to specific interventions and technologies, availability of resources including the competency level of clinical staff, accepted local standards of care, cultural factors and one’s own expertise in the management of CS. Nonetheless, these consensus statements could help create and improve protocols and pathways for the management of CS in centres across the Asia-Pacific region to best benefit patients.

Clinical Perspective

- Immediate point-of-care echocardiography should be considered in patients with acute MI-cardiogenic shock (AMI-CS). Haemodynamic assessment of left ventricular end-diastolic pressure may be considered for guiding therapy. These interventions should not delay reperfusion.

- The stage of AMI-CS, based on the recommendations of this consensus, should be assessed to guide therapy.

- Immediate revascularisation is recommended for AMI patients with Stage B CS.

- Temporary mechanical circulatory support may be considered in AMI patients in Stage C and Stage D CS. For these patients, percutaneous coronary intervention may be considered as the mode of revascularisation.